September - October 2019 Issue

In this issue, we spoke with Ash Gallagher about her upcoming book, took a deep look at our report on threats against women journalists during the first half of the year, and more.

Executive Editor

Kiran Nazish

Earlier this year in january 2019, I joined an advocacy group comprised of different organizations who came to istanbul in support of turkish journalists in prison. It included members of rsf, pen international, some local advocacy groups and us, the coalition for women in journalism. We all came to be present during a hearing for multiple journalists being persecuted by the turkish state. The presence of several international organizations caused the hearing, particularly of erol ozan, that day, to be brief.

The prosecutors and judge, all of whom seemed inexperienced and under the age of 35 wrapped up the hearing quite swiftly, as a turkish journalist told me later, was deliberately done so "To avoid the obnoxious remarks too embarrassing to make in front of foreigners," she laughed. It goes without saying that prosecutors and judge in these turkish hearings, often avoid explicitly displayed the aggression, which is often reported in cases of journalists rights defenders being charged in the country. In the absence of any support or advocacy groups these hearing typical go on for hours and comprise of unfounded accusations, often of terror links and tedious bullying. I have sat in those hearings too many years ago as a journalist.

That particular day there were many reminders that were crystalized for me, as I stood in support of women journalists being persecuted and arrested on insane charges - espionage, terrorism - for doing their job. These courts and prisons that are now frequented by journalists and human rights defenders in turkey were no more doing the job in best interest of the public. They were instead serving the state's agenda to silence free speech and persecute anyone who reveals the ills of the state. As more and more journalists in turkey were sentenced to years long imprisonment, some even life long (read our cfwij reports for more details), for writing a column or a tweet, the messages were clear. A) that judicial systems in countries like turkey were no longer to be trusted to honor and withhold democratic values, they served no more to protect and defend the right of public. B) the fact that today, in countries like turkey, journalists at home needed the support of international groups and media, to embarrass their judicial and democratic systems, meant that we need to double our efforts to discourage governments from targeting journalists. C) that, very predictably, at least for me as I have seen this all along more fifteen years in journalism, women got the least support. At times they got none. Only women journalists who were on the top got any attention if at all, which obviously led them to be persecuted much more easily and harshly.

That day I decided, as the founder of cfwij that we will get more involved in supporting and defending women journalists who are persecuted by governments at the hand of inept judicial systems and corrupt police. This year we have documented every case of harassment or targeting women journalists have encountered, whether by the state or within newsrooms. I am deeply indebted to our wonderful team getting information from the ground from all across the world. I am especially in awe of incredible commitment our research team puts into this work, including luavut zahid, rabia mushtaq and damla tarhan who often work past midnight, or would wake up in the middle of the night to make sure no case in overlooked by us. We work across timezone and in a way, the sun never goes down for us, as we keep an eye open at all times.

This month we are initiating a bi-monthly magazine, so our work can reach a wider community of journalists and the public. Women in journalism monthly, celebrates the work female reporters do across the world, keeps an eye on important events and opportunities and of course, offers an insight into our safety and advocacy related that work we do every day. For more details of any of our work you can view individual reports we publish on our website as they happen. Meanwhile, I hope you enjoy the magazine and send us your thoughts.

Yours,

Kiran Nazish

Founding director

Editor

Luavut Zahid

Developing this issue has been a labor of love. In addition to the work we do every day with helping women journalists find resources and document any difficulties, harassments or dangers they face we wanted to be able to communicate some of the work we do at the coalition along with the amazing work many women journalists do around the world. In this bi-monthly you can find an overview about the data we have been collecting and reporting on, while also find some suggestions for better access to work published by women journalists.

Employers looking to hire can find some excellent candidates - and cfwij mentors and mentee - to hire. With this bi-weekly I hope we can help offer more awareness about how women journalists work in the industry and what the industry itself looks like from their perspective. We hope the insight helps us all understand the industry better and eventually use that knowledge to make journalism a more vibrant, inclusive and safe industry for women journalists.

Index

We are thrilled to announce we will be launching the jSafe App for journalists in the coming month.

Late 2018 the Coalition For Women In Journalism and the Reynolds Journalism Institute came together as a partnership, to develop a safety app called jSafe.

The app has been under development for almost a year now, and we will soon launch the beta version which will be open for testing. The app is to equip women journalists with a safe tool to report a problem. Journalists can report anything from online trolling, physical (or verbal) abuse, or any form of targeting while on the job or after an incident.

How jSafe works: This one-of-a-kind app will allow users to register complaints by choosing various forms of threats they face as journalists and also request a follow-up for their issue by CFWIJ.

The app, which will soon be available on the Apple store for iOS users, boasts a simple user interface that allows them to register/sign-up using their email address. The user will then be emailed a code to complete the signup process. The application has a drop down menu to choose from the types of threats the user has encountered and will also be asked to choose whether they require a follow-up of the case or not. If the user allows follow-up by CFWIJ, their issue will be pursued accordingly.

The application will also contain a section dedicated to useful resources for journalists that might come handy in specific situations.

Half Year Report

In 2019, we documented cases of threats to women journalists across the world. The threats included multiple types of harassment, assault, murders and other forms of violence, including physical and online abuse. Take a look at some of our key findings from the report.

CFWIJ Head-On With Advocacy

Pakistan: CFWIJ’s Pakistan chapter delegation met Federal Ombudsperson for Harassment

On July 17, 2019, the Coalition For Women In Journalism’s Pakistan chapter delegation met with Kashmala Tariq, the Federal Ombudsperson against harassment at workplace.

During the meeting, the ombudsperson and CFWIJ’s delegation agreed to collaborate to help women journalists who are facing harassment at work. The delegation — comprised of leading Pakistani women journalists and CFWIJ members — including the legendary Kathy Gannon. Our members deliberated on the necessary actions required to increase awareness on harassment.

The ombudsperson, Kashmala Tariq, extended her support for the idea and agreed to work with CFWIJ by arranging interactive sessions and seminars to sensitize media about harassment in Pakistan, and ensure a conducive environment. Read our full statement.

Pakistan: Federal Human Rights Minister Shireen Mazari meets CFWIJ’s Pakistan chapter delegation

As part of our two pronged delegation series this summer, The Coalition For Women In Journalism’s Pakistan chapter delegation met with Dr. Shireen Mazari, the Federal Minister for Human Rights. The delegation was an urgent call for meeting with the govt as online trolling and physical attacks against women journalists have grown in the country. Our delegation presented resolutions for the protection of women journalists, in the country. CFWIJ urged the government to investigate the attacks against journalists, especially women journalists, both online and offline, particularly the vicious attacks against senior journalists — our member Asma Shirazi and colleague Hamid Mir. The need for accountability was also stressed upon during the meeting.

Dr Shireen Mazari condemned the attacks and fake news that affect the dignity and safety of journalists in Pakistan. She also assured the delegation about Prime Minister’s position against abuse and violence towards journalists. Read our full statement.

Turkey: Freedom of the Press

We kept a close watch on the state of press freedom in Turkey. CFWIJ’s coverage of three July 18 trials was an in-depth look into the prosecution of journalists in the country.

July 18, was a critical day for free speech in Turkey with three different trials being held at three different courthouses across the country. The trials worked to censor journalists by making an example of the ones who had chosen to exercise their freedom of speech to report on facts.

Those on trial included many members of pro-Kurdish news media agencies, alongside several who have covered protests, such as the one that took place at Gezi Park. The reports are evidence of human rights violations, as well as the lack of freedom of speech and freedom of assembly in Turkey. Read our full report.

Mexico: CFWIJ’s Founding Director invited for multiple events to engage with women journalists and the public.

Our Founder Kiran Nazish was in Mexico this October, where she was a part of a series of events. She started her time there as the Keynote speaker at the FELICH 2019, where she was invited to speak about her career. This was followed by a public conversation on the Dangers Faced By Women Journalists in Mexico and around the world, where she presented the work of CFWIJ.

While she was there the CFWIJ in collaboration with FELICH 2019, organized a roundtable with women journalists in Chihuahua. Journalists from different parts of Mexico joined and discussed the urgent needs for women in the newsroom and in the field. Details of the roundtable will be published by the CFWIJ next month. Her presence brought more attention to support needed by women journalists in Mexico, which were lauded by local press. Read more about it here.

Interview - Ash Gallagher

In the 16 years she's been a journalist, Ash Gallagher has reported from the world’s most challenging places. From covering the plight of refugees in Germany to reporting from war-ridden Gaza and Mosul,

In this interview with the Coalition For Women In Journalism, Ash talks about her life as a journalist in a warzone, who found her way forward in the midst of trauma and a lot more on her memoir Reckoning in the Rubble.

By Rabia Mushtaq

In your writing, from reporting to poetry, you tackle trauma, healing and tap into raw human emotion; how do you channel that into words?

The role of a storyteller is to channel what we all go through as human beings and find ways to communicate those things in our craft. When you think of a film or a song that strikes you, you know the one you play over and again, quote or memorize effortlessly, it’s because you felt it… it resonated with you.

As a writer, I make the same effort. If I can channel what I’ve seen or experienced into a piece of writing, ultimately take the reader with me, then I’ve connected us and connected them, we all want connection — a ‘me too’, so to speak. But it can’t end with trauma. Life is about moving forward, and I want to take the traumas we all face — from war at home to war outside — and say, hey, there’s a way out.

Using grief and acknowledgement, stories themselves can be a path to generating healing. I hope my writing can reflect that. As for my poetry, it’s a raw, gritty look at what we all go through in love, in heartbreak, in our wounds, and in our healing, elevating something deeply connected on a soulful level, perhaps, in a more aesthetic format. The poets were always considered by ancient people to be the storytellers and wise ones, their writings were used to understand the world. Why should it be different now?

“Life is about moving forward, and I want to take the traumas we all face and say, hey, there’s a way out.”

What was the inspiration behind writing a memoir?

I’ve always wanted to write books, I have a few in mind on my life-goals list. But it seemed as good a time as any, and honestly, I was so deeply impacted by covering Iraq, there was more to say, there was more to communicate, so the way to put it down was through a memoir. Iraq is a significant place, an ancient one, where as far back as we know, was the central ground for human development, writing and stories.

It is like ground zero for human civilization in a lot of ways. There’s a story in that which still affects all of us thousands of years later. In a way, perhaps, my memoir is a discovery of how we are impacted by the ancient ground.

Tell us a little about your book, the Mosul Memoir Project: Reckoning in the Rubble?

Reckoning in the Rubble, as I’ve decided to call it a memoir-style series of essays about an awakening and acceptance of self — a sacred reverence for what lies beneath the rubble of war within us all. I unpack themes examining tribalism, the sacred self, accountability and the idea that everything is spiritual and how we all belong. In a way, I suppose, it’s as if I went to the source of where our human record of consciousness began and “got woke.” The book tells my story, nestled in the cradle of civilization; it’s the raw human experience. Examining the effects on mental health, pain and what leads to restoration are themes many can identify. There are no winners in war, but there is opportunity. There is nothing glamorous about being a war correspondent, but there is a journey.

What made you go for crowdsourcing for your memoir and are you getting the support you are looking for?

There are a couple of things at play here. First and foremost, as a freelance writer and journalist, it is hard to take time away from day to day breaking news. We have a mentality about us which struggles to know where our skills fit. So while I still can pick up ad hoc work here and there, if I’m going to concentrate on the manuscript and where It might take me, I need the time to write. And in order to do that, I need to make sure I can eat, sleep and have enough for transport and a cup of coffee. So I have musician friends who have paid for their first albums through crowdsourcing and it’s apparently the supplemental way to find funding in the 21st century. I decided to give it a try. It’s not easy asking folks for support, but if I’m confident in the work, they will be too.

I also worked with an agent for awhile, the publishing houses are competitive. Even ones who were interested, their sales teams would turn it down for one political reason or another.

And that meant it was harder to get an advance or stipend to finish the writing.

I have had incredible support from a lot of good people who I couldn’t do this without, many of them journalists; ironically, who understand and believe in the work. But journalist or not, the folks who have supported have often been unexpected and a complete blessing. That said, there’s still a way to go. Writing is the first stage, then comes editing and publication. And the latter is still up in the air about where it fits, once I finish writing.

Your book is focused on the time you spent reporting from Mosul, Iraq, how you examined the aftermath of war and the spiritual aspect of being in that setting.

Once launched, what impact do you think it would have on the way journalists report in warzones and conflict regions?

The battle for Mosul, really is only the lens for which I am writing through. It is the premise for the story. But the human condition, the way we tell stories, how we all belong and how we all heal is ultimately the goal. Each chapter looks at different aspects of what it was like to cover Mosul and how that translated into my personal life, or perhaps the greater narrative of human existence.

I am a deeply spiritual person, a mystic perhaps, and so I see the depth of how it happens in the physical and how it relates to the soul, to the mind, to mental health and to overcoming tragedy. It’s not an instructional book, but it’s a series of stories, that someone will connect to and hopefully, find a reason to go beyond survival and really live what they’re meant for in this life. But to your point about impacting journalism, I have some hope it will challenge the industry to think more about solution-based reporting. We spend a lot of time on traumas, the number of dead and the tragedy of what happens in war or political situations.

And yes, there’s some great stories out there, but they’re not mainstream and even the analysis on-air is paid pundits to debate the latest tragedy. No one in the audience is listening, or if they are listening, they’re becoming more divided because that’s what they see and hear.

Yes, we as the media have a huge responsibility in informing and identifying solutions to the tragedies in the world, and even more importantly, we have a responsibility for connecting people.

How does it apply to them? People tell me every single day they turn off the news because it doesn’t apply to them and it’s too far away. But what if weren’t? What if I showed you what you have in common with a woman in Iraq whose husband beat her and ran off to shoot people and join a militia? Sounds familiar?

What if neglecting USAID and putting more money into weapons not only affects your pocket book but could cause your son or daughter in the military to miss Christmas this year? Maybe even their funeral? Do you care a little more? I bet. Or what if I could show that your tribe — family, politics and social status — is no different than the ones you call the enemy and maybe there’s room for peaceful negotiation?

What if reconciliation was really possible and we didn’t have to be so divided? Let’s do that because the war stories, the trauma, can’t just be reported because it’s there, it has to move forward somehow.

Warzones are not the most pleasant places to report from. Witnessing people suffer, especially children and women, can take a toll on one’s mental health. What was it like for you?

I have long said, it wasn’t the dead that bothered me so much. They no longer added to the story, it was the living. Their stories and energy, impacted me a lot. As a journalist, it’s my job to hold space for what they want to say. And if it's a tragedy they need to tell, then so be it.

In fact, it is a part of my job to help guide them with the questions for which I want answers, the ones I deem important to understand the story or the trauma better. But holding space for so many, some I may never see again, can be a heavy task.

In the moment, I turned myself off or deflected the heaviness of that sadness, just so I could be engaged, listen and do my job.

But afterwards, I always came away with a need to release. The body, mind and soul are connected and so what I felt in terms of sadness or frustration came out in the ways my body expressed itself.

So while I’m not a stranger to insomnia, war created a few more sleepless nights and there have been moments, I’ve needed to isolate myself to scream into a pillow or weep. But I’ve also found something else — covering war can also be enlightening.

“I have long said, it wasn’t the dead that bothered me so much. They no longer added to the story, it was the living. Their stories and energy, impacted me a lot. As a journalist, it’s my job to hold space for what they want to say. And if it’s a tragedy they need to tell, then so be it.”

But I’ve also found something else — covering war can also be enlightening. When I began with the intent to understand the human condition better, I found it, war isn’t always the worst of humanity.

Sometimes, war showcases the best of humanity. People are resilient through tragedy.

I say now some of the most enlightened ones are the mothers who get up off their mattresses everyday in a refugee camp and find the strength to feed and bathe their resilient children, who are often playing outside and laughing. So I learned a great deal from them.

War can take its toll, but war can also enlighten us to who we really are and what we want to become. Bearing witness to war isn’t just about suffering; it’s also about waking up to our very real primal condition and what makes us radically divine beings.

FEATURE ARTICLE

WOMEN BEHIND THE LENS

Seeing Pakistan Through The Female Gaze

By Rabia Mushtaq

Having worked as a journalist for a weekly magazine, I often found myself covering a variety of events like book launches, press conferences, seminars, fashion shows, festivals and much more. Throughout my time on the job, I got familiar with some of the many popular photojournalists who closely, and particularly, worked within the entertainment industry in Karachi, Pakistan. But something always left me curious — I barely ever came across women photojournalists.

In Pakistan’s journalism industry, women often outnumber men in newsrooms as deputy editors and sub-editors. They also work as reporters on the field. But when it comes to photojournalism, male photojournalists can be seen thronging red carpets and taking up the best spots, especially during fashion weeks.

In the era of Instagram and popular online platforms, one may come across talented Pakistani female photojournalists. But sadly, the situation on the ground is different.

The lack of female photojournalists in Pakistan can only be guesstimated given that there is little to no data or information – official and otherwise – that could keep a count of how many women have worked and are working as photojournalists in the country.

Following cultural restraints, sexism at the workplace, discrimination and harassment both on and off the field, as well as the deep-seated misogyny and patriarchy in the society, women with cameras at the frontlines are still not a common sight in Pakistan.

So I decided to dive into the matter to find out where the women are, and speak with those who are breaking the barriers and striving to receive the same professional dignity and opportunities their male counterparts get in the industry.

In a video shot for The Coalition For Women In Journalism (CFWIJ) Sara Farid, a Pakistani photojournalist and CFWIJ member, shares that she was often the only woman with a camera when covering several press conferences and events in Pakistan. She calls the profession “a big boy’s club”.

“You’ll feel alone. You’ll feel like you’re being cornered and feel like there is no moral and physical support. You cannot enter the boys club because there’s a lot of sexism that exists in this industry, even in newsrooms by editors; you face character assassination and a lot of other issues,” she says, adding that one has to be strong and somehow, make it work for themselves.

Most of Sara’s work is focused on women’s rights, and religious and sexual minorities in Pakistan. Her passion for the work and success as a photojournalist is obvious.

“Growing up as a woman in Pakistan, all of us have faced some sort of bias, harassment, violence and abuse, and it makes you feel that you need to become a voice for all those people who face discrimination and violence, and you need to give them the space to talk about their issues,” says Sara, who then proceeds to share how being a woman has given her the opportunity to focus on various issues. “It’s important to talk about issues. As a woman I have access to these communities and I’m able to photograph them.”

Like Sara, Karachi based Malika Abbas Nosherwani has been working as a photojournalist since 2009. She works for White Star Photo – a photographic firm associated with the Dawn Media Group, as well as digital magazine Womanistan.

Talking about her experience as a female photojournalist for 10 years, Malika says it has been a good one, in general. “I haven't faced discrimination; in fact, a female photojournalist is sometimes preferred over a male photojournalist when it comes to women centric assignments,” she says. However, she does agree with the lack of representation in the industry. When asked why more women don't pick up a camera in Pakistan, she said, “Photojournalism is not a lucrative business to be in. And it involves being in places and situations where most women would not want to be and even if the women don't mind that, their peers don't want to be held accountable and responsible (in case of unforeseen consequences). Therefore, it takes a while to convince people that you are serious about this profession and are willing to put your 100% into it.”

During the course of my exploration, I connected with independent photojournalist Saba Rehman. Saba has been working for the past seven years and is the only female photojournalist working in an otherwise conservative province of Pakistan – Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Having worked with both, local and international publications and digital news websites including behemoths like BBC, DW, Arab News, Al Jazeera and TRT World to name a few, Saba, too, says that she is blessed to have not faced gender discrimination following the support of her editors. However, she says that the number is rather low when compared to male photojournalists.

“There are no permanent positions for female photojournalists in any international publications in Pakistan. Even though the number of men are also inadequate, but the absence of women photojournalists as permanent staff largely remains an issue.”

From stories focused on female inmates to drug addicts and women empowerment to elections in the country, Saba mainly works in tribal regions where even men have a hard time covering news stories and photography.

“There are a lot of issues for journalists and photojournalists when working in Pakistan, particularly in the tribal regions up north,” Saba says adding that safety remains a point of concern.

“People don’t know what photojournalism is, while society’s lack of acceptance for the work, as well as restrictions by law enforcement agencies, can sometimes act as hurdles.”

Another tough battle that female photojournalists encounter is growing sexism in the industry. Saiyna Bashir, an Islamabad-based photojournalist who works for several international news outlets and agencies, talks about an instance when a male colleague was preferred over her to cover an event.

“They sent him to cover the Women’s March. Even though I could’ve done a much better job at it,” she shares and adds, “There is plenty of sexism, of course. Because everybody says ‘You’re a woman how can you carry so much gear and aren’t you tired’.”

Nevertheless, Saiyna’s work speaks for itself despite the discrimination she faces when doing her job.

“Following my diverse portfolio, my editors now do not specifically assign me for a specific story. From travelling alone in remote areas to covering a bomb blast at the Chinese consulate in Karachi, I get to work on various challenging assignments," she shared.

A budding female photojournalist in Karachi, Manal Khan, has also tackled sexism in the field.

“In 2017, I visited a mosque for an article on the importance of its architecture. As soon as I reached the gate, the security guard stopped me and refused to let me enter the mosque. I was wearing a long kurta and my head was covered when this happened,” she recalled.

“Even the media group I worked for was male-dominated. They only contacted female photojournalists for women centric projects or where men aren’t allowed to enter,” she said.

Giving women equal opportunities in the photojournalism industry is as crucial as providing them their deserving position in the newsrooms.

One may never know what the odds are for women photojournalists in Pakistan but support is never out of the question. As an organization invested towards supporting and mentoring women journalists across the globe, the subject becomes much more relevant for The Coalition For Women In Journalism. The need for women photojournalists will always remain imperative. The ideas and skills that women can bring to this profession is incomparable to what their men can manage.

Having a member like Sara Farid, who is one of the best Pakistani women photojournalists, CFWIJ looks forward to see more women challenging deep-seated norms in the country.

Both Sara Farid and her husband have been living in France after they received security threats in Pakistan. The change of place and work dynamics made it difficult for Sara to pursue her professional aspirations as a photojournalist, which is when she says the aspect of support became crucial to her life.

“Right now, the Coalition’s work is most useful for me… through CFWIJ’s platform I’m meeting new people, getting connected to journalists who work in Europe and other countries. It’s a great opportunity to be a part of the coalition and figure out my future plans,” she said.

CFWIJ upholds the importance of women’s voices in every aspect of journalism. As photojournalists, their visual creativity can be unfathomable and it’s only a matter of opportunity and consideration towards their talent.

Only 15% of news photographers around the world are women according to a study conducted by World Press Photo and the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Another organization, Women Photograph, shared that less than one in five lead news photos published across eight popular news titles are photographed by women photojournalists.

This is the situation around the world. The numbers are likely worse in South Asia, especially in Pakistan, where journalism is a male-dominated field.

It is imperative to ensure that photojournalists and visual storytellers are as diverse as the subjects they choose to cover.

As far as society is concerned, Pakistan may be relatively backward with respect to an ample number of photojournalists, but the women photojournalists we spoke to have set an example for many to enter the industry and prove how representation matters.

Roundup Of Threats Women Journalists Faced Between August - October

In the past month, the Coalition For Women In Journalism documented various threats to women journalists around the world. From documenting arrests of Iranian women journalists to attacks on freedom of speech and expression in Turkey, and not to forget the travel ban on Majdoleen Hassouna — a Palestinian woman journalist. Here’s a round-up of everything from journalist’s safety to curbs on women journalists’ voices from the past month

State of press freedom in Iran

The Coalition For Women In Journalism monitored the state of press freedom in Iran last month, specifically the authorities’ treatment of women journalists.

According to the World Press Freedom Index, the country slipped six places down to 170 among the 180 countries on the Iist, following the arrests of journalists and activists with charges like jeopardizing national security among others.

Iran also came under strong criticism for being the world's biggest jailer of women journalists with 12 currently imprisoned for their reporting of human rights violations and coverage of protests against state policies.

The strict censorship policies of the Iranian government and prosecution of journalists was highlighted by CFWIJ in the form of its detailed report on imprisoned women journalists in the country.

Travel ban on Palestinian journalist

On August 18, a Palestinian journalist Majdoleen Hassouna faced a travel ban by Israeli authorities in West Bank.

The journalist — who works for TRT’s Arabic service — was attempting to return to her office in Istanbul, Turkey.

Majdoleen was visiting her hometown Nablus to spend Eid with her family, but when returning to resume work in the Turkish city, she was first detained by Palestinian intelligence. After being released by them, the Israeli authorities detained her for hours at a checkpoint and told to return back to Nablus; banning her to travel from thereon.

The journalist has had skirmishes in the past, but this was the first time she faced a travel ban. In July 2018, Majdoleen was physically assaulted by Palestinian security officers during a protest in Tulkarem, West Bank.

Turkey’s curbs freedom of speech

In the month of August, a court in Ankara ruled in favor of blocking access to 136 websites and social media accounts on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram and Pinterest. An independent and bilingual online news platform, Bianet and ETHA (Etkin Haber Ajansı) — a left-leaning news agency, also came under fire during the clamp down.

The decision to block Bianet was later reversed by the court that deemed it a “mistake”. However, the rest of the platforms still remain inaccessible and reflect the Turkish authorities’ deliberate attempt to restrict press freedom.

We kept a close watch on the state of women journalists in Turkey. According to our data, 11 women journalists are currently imprisoned in different Turkish prisons. We continue to urge the authorities to release all women journalists who are behind bars only for doing their jobs.

Moroccan Journalist imprisoned for ‘abortion’ pardoned

On October 16, Moroccan journalist Hajar Raissouni was pardoned by the country’s King Mohammad VI. She was arrested, jailed and eventually sentenced for a year for allegedly having premarital sex and having gone through an illegal abortion, both of which are punishable crimes in the Kingdom.

Hajar and her fiancé were arrested after stepping out of a clinic in Rabat where, according to Hajar and her doctor, she had gone to get her blood clot treated. The doctor and his two aides for complicity in the crime.

The government of Morocco faced severe backlash regarding their interference in an individual’s personal life, as well as their intolerance towards independent media.

While we welcome the release, it’s still worrying that she was pardoned and not released because she was not guilty of a crime.

Turkish journalist evades 15 year sentence

Former reporter of pro-Kurdish Jin News Agency, Beritan Canözer was released by Turkish authorities on October 16. She was arrested and charged with “terrorist group membership” and “terrorist propaganda” after covering a protest during the curfews in Sur, Diyarbakir.

Beritan could have been given up to 15 years in prison had she been convicted. Her acquittal has been attributed to witness testimonies, according to her lawyer Resul Tamur.

The prosecution insisted the court to sentence Beritan for 15 years in prison; however, the 9th High Criminal Court acquitted her.

The CFWIJ has welcomed the decision and hopes that the authorities will continue to let good sense prevail.

Turkish journalist Kibriye Evren’s jail term upheld

Languishing behind bars since October 9, 2018, pro-Kurdish agency Jin News’ reporter Kibriye Evren’s imprisonment — up to 20 years in prison — has been upheld by a local court in Diyarbakir. The order was recently given at the seventh hearing of the case at the 5th High Criminal Court on September 25.

She was arrested alongside 142 other journalists and politicians last year and was charged for sharing posts on her social media, which also included a picture of the journalist at a picnic.

Kibriye has been in jail for more than a year now and has complained of living in deplorable conditions. Mice droppings and shards of glass were found in her food, while the she has also stopped receiving stationary for her letters and books.

The next hearing for Kibriye’s case is scheduled to take place on November 12.

Turkish columnist Nurcan Kaya placed under travel ban

Nurcan was originally detained at the airport when she returned from another country on October 27. She was interrogated and sent on her way. She tweeted that she had been taken in for inciting the public to hatred.

The issue stems from a Tweet she put out against Turkey’s operation in Syria. Turkish authorities have upped the ante on crackdowns on Kurdish journalists or those they feel are partial to Kurdish narratives. This has led to renewed attacks on freedom of speech in the country.

After being released, Nurcan was told that she was being slapped with an international travel ban. She is being represented by the MLSA, which will be appealing the ban.

Russian journalist Yulia Yuzik released from Iran

After being detained for more than a week, Yulia Yuzik was allowed to return to her home. Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) took her passport when she landed in Tehran. She was later arrested from her hotel room on September 29.

While the Iranian government maintains that Yulia was arrested for visa violations. Yulia’s ex-husband reported that she was targeted because the authorities suspected she has connections to Israel’s intelligence services. The journalist herself believes she was targeted because of her Jewish surname.

She was previously stationed in Iran as a journalist, and has lived in the country. While in custody, she was not allowed legal help or counsel. She was able to find her way out because of the intervention of the Russian Foreign Ministry.

Badass Women Authors

On October 5, 2017, CFWIJ’s advisor Jodi Kantor and her New York Times’ colleague Megan Twohey published an expose that completely changed the way how the world viewed sexual harassment of women, especially in Hollywood. The two Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists brought to light Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein’s treatment of women, by convincing the victims — both famous and unknown — to go on record. Both Jodi and Megan made history by writing a gritty, investigative piece of journalism for the NYT.The duo is now back with a gripping account of their reportorial journey about how they managed to get to the core of the Weinstein story, which reignited the #MeToo movement in the US.

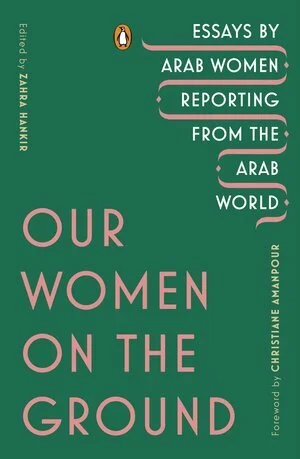

Edited by British-Lebanese journalist and writer Zahra Hankir, Our Women on the Ground, is a collection of personal essays by women journalists who have covered news and events in the Middle Eastern region. From sxism to the cost of war and conflict, the essays reflect what these women have tackled to fulfill their professional commitments.CFWIJ’s member, Hwaida Saad, also shares her experience by shedding light on the Syrian crisis that began in 2011. Hwaida notes down the changes in her interpersonal relationship with the sources in Syria with time, following the revolution’s transformation into a civil war;and writes about the way innocence gradually disappeared from the country.We highly recommend this book for its effort.

Sady Doyle reflects on why women are seen as monsters, how the stories convey and underline fears about women’s bodies, the way women resist and the idea of women possessing power. Ranging from classic myths and fairytales to contemporary horror stories, the book is based on monster tales and true crime stories.

Deep down the surface, the book highlights gendered concerns, dealing with sensitivities regarding a woman’s place in a society obsessed with patriarchal values.Sady brings forth the monsters that symbolize the patriarchal fear of women; how the notion of women being powerful frightens patriarchy and seems supernatural.

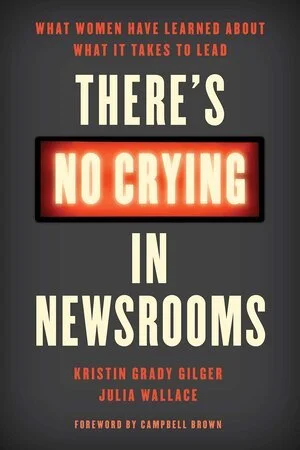

Dealing with sexual harassment, understanding newsroom culture, balancing work and life, or finding one’s way to leadership — this book shares the stories of women who have remarkably overcome such challenges while working for media organizations in the US. Through labor pains and raising kids, these women have called in news stories and fought battles to get where they are now. The same battles they now see the younger lot of women journalists facing 40 years down the lane — albeit with way less preparedness. There's No Crying in Newsrooms teaches lessons on what it takes for one to succeed in the media or any organization with men dominating the hierarchy and the female pioneers share their years of experience of surviving and challenging the system.

Women's anger around the world is palpable. But too often it is dismissed, suppressed or acknowledged only through the lens of how useful it is too society. In the new anthology Burn it Down, published in October by Seal Press, editor Lilly Dancyger aims to demonstrate that women’s anger “doesn’t have to be useful to deserve a voice.” Highlighting the rage of 22 contemporary women writers, Burn it Down features a collection of fiery essays that Kirkus Reviews calls “Powerful and provocative, this collection is an instructive read for anyone seeking to understand the many faces—and pains—of womanhood in 21st-century America. Among the pieces highlighted by Kirkus is CFWIJ mentor Shaheen Pasha’s essay “The Color of Being Muslim” in which Pasha “talks about her rage at 'the suffocating expectations of others,' both within and without the Pakistani American community, who saw her as being too Muslim or not Muslim enough.”

CFWIJ In The Press

Turkish Online News Platform Sendika Calls Cfwij “A Cross-border Support Network For Women Journalists.” In This Extensive Interview With Our Founding Director, Kiran Nazish, Sendika Finds Out About The Organization’s Activities, Objectives And Issues Facing Women Journalists Around The World. Read The Full Interview.

Our Founding Director, Kiran Nazish, Was Interviewed By Sivil Sayfalar — A Turkish Online Platform For Civil Society Organizations. Kiran Talked About The Challenges Faced By Women Journalists Around Globally And Cfwij’s To Support Them. She Also Talked About The Mentorship And Advocacy Work Being Done By The Organization Across All Its Chapters. Read The Full Interview.

The Coalition's Work Was The Topic Of Discussion. “The Goal Is To Create A Support Network For Women Journalists Around The World,” Founding Direction Kiran Nazish Said In An Interview To A Turkey-based Bipartisan Media Organization, Journo. Read The Full Interview.

In Focus

Dutch Journalist Clarice Gargard was at the UN recently. This is what she said.

Women Journalists You Should Hire

Editors, employers and colleagues looking for recommendations, here are some women journalists covering stories on the ground with the expertise and insight that may significantly improve the quality of journalism you are looking for in the said countries. If you'd like us to help you get in touch with them, shoot us an email.

Looking For A Journalist In Mali?

Hire, Our CFWIJ Fellow Annie Risemberg.

Annie Is A Documentary Photographer And Photojournalist Based In Bamako, Mali. Annie Began Her Career In Philadelphia, U.s.a. And Later Moved On To Foreign Reporting Freelancing From Different Parts Of Africa. Annie Has Reported Deeply From Accra, Ghana Publishing With Al Jazeera English, Bbc, Reuters, Agence France-presse, Bright Magazine, Roads And Kingdoms, And Open Society Foundations. Annie Has Exhibited Her Work At The 5th Edition Of Addis Foto Fest In December 2018. She Is Currently A 2019 National Geographic Grantee For Her Work With The Sufis In Mali. You Can Virtually Meet Or Listen To Annie Speaking About Her Mentorship With The Coalition Here. Annie Was Mentored By Several Mentors With The Coalition And She Has Access To A Wide Network Of Journalist Through Our Group.

Work >

Twitter >

Looking For A Journalist In China? Hire, Our CFWIJ Fellow Betsy Joles

Cfwij Fellow Betsy Joles Is A Freelance Journalist Based In Beijing And Occasionally Follows Stints In Istanbul, Beirut And Kuala Lumpur. Her Work Focuses On The Important Subject Of Diaspora And The Human Side Of Geopolitics, As She Connects Threads Between The Middle East And East Asia. Betsy Also Works As A Contributor To Getty Images In China.

Work >

Twitter >

Looking For A Journalist In Mexico? Hire, Our Cfwij Member Natalia Cano

Natalia Is A Freelance Journalist Based In Mexico City. She Has Worked As A Reporter And Photojournalist Over A Decade. Her Expertise Lie In The Culture And Entertainment Beat. Natalia’s Journalistic Work Sometimes Also Focuses On Social And Political Stories From Mexico City. Her Work Regularly Publishes In Some Of The Leading Local And International Spanish Publications Including The El Universal Newspaper, Notimex, Sin Embargo Mx And Associated Press In The Past, And Currently Contributes To Afp Mexico And Rolling Stones.

Work >

Twitter >

Looking For A Journalist In Afghanistan? Hire, Our Cfwij Fellow Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska

Our Fellow Agnieszka Pikulicka-wilczewska Is A Freelance Journalist From Uzbekistan And Has Widely Covered Eastern Europe And Central Asia From The Right Wing Rallies To Some Tough Conflict Related Stories. Agnieszka Has Recently Been Based Out Of Afghanistan. Her Work Is Focuses On The Post-soviet Regions, Central Asia And The Far Right. She Has Worked As The Editor Of New East Europe And Works Published In Al Jazeera, Eurasia Net And Moscow Times Among Others. Some Thoughts From Agnieszka About Women Journalists In The Industry. Agnieszka Has Been Mentored By Charlotte Alfred, One Of The Finest Journalists On Migration Who Was The Managing Editor Of Refugee Deeply And Is Currently A Journalist Based Out Of London And Kiran Nazish.

Work >

Twitter >

Report Safely: Secure Messaging Apps

Secure Messaging Apps We Swear By

Signal

I first heard about Signal during a digital rights training for journalists and instantly downloaded the app for its Open Whisper System protocol, which makes it super safe with end-to-end encryption.

Steer clear of spies! The app lessens the amount of data or metadata left behind by each of your messages.

You can text other Signal users in your contacts, make calls and send self-destructing messages that don’t last long during a conversation.

You may wonder if an app like Signal may cost you a fortune. Not at all! It’s absolutely free to download for both Android and iOS users.

Bonus point: NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden calls it the most secure messaging application. Need we say more?

Telegram

Need speed and security? Telegram is made for you.

Keep all your communications safe with its ‘Secret Chats’ feature — perfect for journalists working on sensitive stories.

You don’t need to worry about your conversation being misused. Once deleted by a user, messages vanish on the other side of the chat too. Use the self-destruct feature for photos, videos and files, even after they’ve reached the recipient.

Stay out of the cloud with Telegram. Your chats can only be accessed from the device you use. So if your device is secure, your secret chats are completely secure.

Telegram is blocked in some countries like Pakistan, China and Russia among a few others. So that’s a downer, unless you’re using a VPN connection.

Threema

If Telegram isn’t working in your region. Threema can be your savior but it’s a paid app.

With the end-to-end encryption and ad-free features, the app is a good deal and doesn’t rely on investors that may cause conflict of interest.

The app generates as little data as possible, so stop worrying and start communicating.

Messages are immediately deleted once delivered.

Groups and contacts are managed on users’ devices and no meta data is collected.

Tired of a tedious registration process? Chat anonymously using a random Threema ID, no personal info needed.

Threema keeps your communication safe with features like sending text and voice messages, files and locations in group and single chats.

·The app also is a great way to make voice calls and create polls.

Tips: How To Identify Fake Videos

Identifying a Fake Video

In this YouTube and WhatsApp-obsessed world, many media outlets and journalists end up making news stories using viral videos. One of our colleagues recently came across a sketchy video that seemed too unreal to be turned into a news item. If you’ve come across a video that seems vague, here’s how to identify if it’s worth turning into a story.

Observe

Look for anything that you feel is unusual in the video. Many videos may seem real but strange. From hydrographic printing to people diving down tall structures, the surroundings often give away minute details.

Check for inconsistencies

Download the video and repeat to check for any form of inconsistencies that you may otherwise not notice in one go. Visual effects and manipulations can be identified if watched closely. Blurring of the video at places, shadows and reflections are telltale signs to identify fake from real.

Look for the source

Even after looking for reliable coverage, you may find the video fishy. Google whatever you see and check for similar coverage of the news. Reliable websites and the language they use give away clues. Search for similar video titles to check if it has been posted before or not. Do a Google reverse image search of the video’s thumbnail. Check for the video uploaders’ online presence and genuineness. The duration of their account’s active status and their interaction with users is also helpful.