October 2020 Issue

This issue features interviews of journalists Zahra Rasool and Grace Panetta, focuses on pretrial detentions in Egypt, and includes a report about women journalists imprisoned around the world. Go read.

Editor’s Note

Hello readers!

We hope you all are staying safe, healthy and aware.

This month, we greet you while anticipating the results of the US presidential elections. October was packed with news coming in from all corners of America. Following the buzz around elections, we had a Q & A session with Business Insider’s politics reporter Grace Panetta, who shared with us about her experience reporting this monumental event, how she pulled it through despite challenges in the midst of the novel coronavirus outbreak, and reporting in times of fake news, misinformation and disinformation.

We also interviewed journalist Zahra Rasool, the head of AJ Contrast. Zahra is a well-known name in the field of immersive/innovative storytelling and journalism. In this interview with CFWIJ, Zahra talks about the use of immersive/innovative technologies and making it accessible to the audience, how important it is to tell stories that matter, the significance of transparency over objectivity in journalism and lots more.

Samar Elhussieny, our MENA and Turkey research coordinator, writes about the unjustified trend of pre-trial detentions in Egypt. In her piece titled ‘Pretrial detention – the Sisyphean Misery in Egypt’, Samar includes cases of journalists who’ve been arbitrarily held in detentions for their work. Many of these journalists are practically thrown inside jails and awaiting fair trials. Read more about it in this month’s issue.

The issue also includes a report on women journalists imprisoned around the world. Thirteen countries around the world have arbitrarily locked at least 38 women journalists behind the bars. From Iran to China and Turkey to Vietnam, these countries have incarcerated them for their reporting on crucial issues.

With US presidential elections in news, we decided to feature four women journalists reporting the event in our Women Journalists To Follow section. A diverse set of journalists including Alexa Corse, Jane Lytvynenko, Catherine Kim, and Briana K. Stewart share some much-needed insight and updates to keep you in the loop with all that’s happening in the world of US politics.

This month, CFWIJ recorded at least 540 cases of threats and violence against women journalists. Find our regular section featuring a round-up of cases in this month’s issue. You can also access our monthly report here.

To stay updated on discourse surrounding US politics and current elections, listen up to our recommended podcasts and also find some insightful books to read this month.

To share feedback and suggestions, reach out to us via press@womeninjournalism.org

Adieu!

Kiran Nazish, Executive Editor

Rabia Mushtaq, Editor and Writer

Damla Tarhan, Design

Samar Elhusseiny, Contribution

Index

Interview

PHOTO CREDIT-ASIYA KHAKI

Zahra Rasool: A Force To Reckon With In The Innovative And Immersive Storytelling Space

By Rabia Mushtaq

Technology. This word rules our life as much as the term ‘fake news’ does these days. But many people around the world are still trying to wrap their heads around the idea of the former taking over their lives in almost every aspect. From once making calls to now communicating via AR, the use of smartphones and other technology products have left humankind in awe of its power.

These groundbreaking developments have also made their presence felt in journalism. The idea of making their audience experience the feeling of ‘being there’, using innovative and immersive storytelling techniques in modern journalism, is what journalists today are getting pro at. The use of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) is no more just a thought. Young and driven journalists are challenging themselves each day to bring something new to the table. Zahra Rasool is one of them.

She comes across as a millennial who is winning her game. Her passion for journalism reflects through her innovative take on storytelling. As the head of AJ Contrast — Al Jazeera's award-winning immersive storytelling and media innovation studio — it makes sense how Zahra’s contemporary style of work has been winning praise around the world. It is remarkable that someone as young as Zahra is at the helm of all the brilliant stories produced at AJ Contrast.

“It is actually pretty tough to be honest. The job seems very interesting, cool and exciting — and it is in all those fronts, but it is also very hard to do anything innovation related within the journalism industry,” Zahra said when asked about leading AJ Contrast and the responsibility that comes with it.

“As most journalists are aware, budgets for journalism work continue to shrink every year. Therefore, to prioritize anything innovation related or niche is very difficult,” she added.

Before Zahra turned into a juggernaut, she was already a media entrepreneur who built her own start-up named Gistory in 2015. It was part of her master’s program, which she pursued after quitting her job as an investigative journalist for Al Jazeera’s broadcast show. Zahra worked on her start-up for an entire semester, presented it at a journalism conference and received immense attention. Her journalism school funded the start-up, which she pursued full-time for the next three years. She deemed it as a “phenomenal experience”.

Raising money for her start-up as a Muslim and immigrant woman of color became increasingly challenging for Zahra, so she put a pause to it and began working as a managing editor at the Los Angeles based RYOT — the first company to use AR and immersive texts in their stories, which was later acquired by Huffington Post.

In January 2017, Zahra joined Al Jazeera and created AJ Contrast to cater to the network’s digital audience. Three months later, it was launched and the platform has since focused on innovative ways to produce quality journalism and storytelling using immersive technologies.

“When doing a story, AJ Contrast’s mandate is to find a more creative, captivating and immersive way to tell it. A good example of that would be our recent interactive web experience Living in the Unknown — a story about the Uighurs, living in exile in Turkey. We created this interactive web documentary and also added a VR component to it. But we just wanted to be able to tell this story that is incredibly urgent in a way that hasn’t been told before,” Zahra said, emphasizing on the way her team focuses on crucial stories using technology.

One wonders how many people actually end up becoming an audience to these technologically advanced stories, as accessibility remains a crucial hurdle in many places around the world.

“It has been the toughest part of working in the innovation space because when we are doing innovation work, we are only thinking of the privileged. But working at a place like Al Jazeera is interesting because so much of its audience is the developing world and we are forced to confront those questions. One of the philosophies of AJ Contrast is trying to train and invest in storytellers in those parts of the world because they are going to the best advocates for making sure that those stories and those ways of storytelling can reach their audiences,” Zahra said.

She added that while she can give a talk or lecture on VR, AR and accessibility, it would be very hard for her to parachute into a location. But since she is not living in those locations, she cannot commit and work on those barriers of accessibility.

“It is the people living in those countries who would actually be able to do that. We work with a lot of storytellers from around the world. Almost every story that we have done, whether it is from Yemen, Congo or any other country shown in our stories, we work with local talents. This helps us widen the pool of the people who know how to use this technology. A lot of times the people that we are working with do not know anything about VR or 360 video, most recently AR,” she informed.

Zahra shared that her team works at the backend to equip them, send them the technology and mail cameras when needed. They train them online using Skype, WhatsApp, Messenger and similar means. They also offer instruction manuals translated in several different languages.

“We put in a lot of time and effort into that, even though the output is a lot less. But I do not need to have a certain number of videos and stories out because the work that we are doing at the backend is more important than us seeing a story coming out of it,” she explained when sharing how the platform is working to lessen the accessibility gap.

Zahra added that another way to do that is via screenings in different places.

“We have arranged VR screenings in different countries where we have done the videos. For instance, we held a screening for people at the Zaatari refugee camp, who worked with us on the videos about the camp. We did it for them to understand and see the video in VR. We did the same in Lagos and Nigeria too. It is limited, but based on our capacity and the small team, this is what we are able to manage,” she shared.

With Zahra leading the platform and the hard work of her dedicated fellow team mates, along with locally hired storytellers, have produced some of the most urgent, impactful stories of conflict and underrepresented communities using immersive technologies.

Still Here, an immersive multimedia installation tells the tale of a Black woman based in Harlem who experiences incarceration for 15 years and comes back home to witness gentrification of her community in the neighborhood and meets her teenage son after spending years away from him. This story was showcased at the Sundance Film Festival in February this year. While Living in the Unknown, the story of Uighur Muslims who escaped from China, won in the Excellence and Innovation in Visual Digital Storytelling (small newsroom) category.

As someone hailing from a Muslim immigrant family from the Indian cosmopolitan Mumbai, it was Zahra’s goal to focus on similar stories to share them with the rest of the world and the reason why she pursued journalism.

“I grew up at a time when the war in Iraq and Afghanistan was all they were showing on television (TV). The images that one saw on CNN, BBC or any international media were of Muslim people who looked like me, felt like me and shared a very similar culture. But the narratives being shown were so distant from my experience. I grew up seeing them speak about and show Muslims in a negative light. It felt like a disconnect between what I saw on TV vs. my lived experience,” she recalled about the state of Muslim representation in international media from her younger days.

Zahra shared that when she started working in this field using immersive technologies, she felt that the skill set to use these technologies were in the hands of very few people, who were often white men. She added that the stories were being told from their lens and for their interests. This felt exploitative and voyeuristic to Zahra and she felt jaded.

“Interestingly, there are a lot of women in the immersive field. But in terms of diversity, it is hard to put a number. During my Sundance experience, the majority showcasing their projects in the immersive space were white. The space is still, of course, heavily white and male. This is also because the skills and software required for development, technical development of the AR and VR experience, and post-production is expensive,” she said.

Zahra stated that one ends up being skewed more towards not just white but mostly privileged people who are creating these experiences, which is why she made AJ Contrast’s mission to work with mostly people of color.

Zahra is a Muslim woman of color and covers her head with a scarf. When talking about dealing with tokenization and discrimination in the industry she explained that her identity as a woman cannot be separated with her identity being a Muslim.

“This definitely impacts most of my interactions. I constantly feel like I have to work so much harder than my peers and those around me. I am also frustrated when I do something successful and then for my next project, it is required for me to prove that it is good enough to get the funding and support. People don’t judge me based on my past work,” she said.

Zahra added that it is challenging for her to get the funding, as people are always interested in the ideas but it never translates into handing money.

“Most people who are giving the money hire and support those who look like them and support their ideas, who they think will be able to carry their project and make something successful. I don’t fit their idea of somebody who could lead a big project or program,” Zahra complained.

During the conversation on tokenization, she shared about being in situations and jobs where organizations in the past took her onboard as their diversity hire and because it makes them look good.

“It really affected my confidence and hurt me, because I was only there as a diversity person. They did not necessarily think that I was equally skilled or qualified, even though I am. But as I grew in the profession and gained confidence, I realized that this is just how the world works. If this is the opportunity given to me, I have to ensure speaking my truth, serving to the best of my abilities and capitalize the opportunity. I am less affected by it now then I was back then,” she said, adding that it is still frustrating and hard to deal with.

Expanding on our discussion on diversity in the immersive field, Zahra mentioned how the offer from Al Jazeera was an opportunity for her to bring some change in the industry and counter the typical narrative. She requested control over editorial in order to serve people from underrepresented communities and those hit hardest due to inequality by bringing them into the process of creating those stories, as well as collaborating with them.

Following Zahra’s work and the topics she brings to the fore through her journalism, it is evident that being transparent as a journalist is more crucial to her than merely focusing on objectivity.

“As human beings, we come with our own preconceived notions, biases, culture and experiences. Whenever we are reporting or telling a story, all of those experiences shape that particular story. Therefore, I don’t think we can be objective, but we can strive to be. We should strive for more transparency in everything we do to make sure that our audience knows where we are coming from,” she opined.

When working on stories in different places around the world, the platform collaborates with people on the ground, which is why Zahra shared that they cannot simply expect these individuals to be objective. It is important to consider the sensitivities and experiences of people who live amidst those ground realities.

“If we are collaborating with someone who has lived through the war in Yemen, we can’t possibly expect them to be objective. We are going to talk about the story from the experiences of utter devastation and suffering they have experienced. This is completely fair, as we are going to let our audiences know that the person reporting on the story has experienced the situation and give them the background,” she said, while also adding that a lot of young journalists think that way. That they are now moving away from the conversation of objectivity and focusing more on transparency.

Before Covid-19 affected the workflow of most organizations around the world, Zahra and her team planned to travel around the country for their now halted series on the US presidential elections called Color of my Vote, which was focused on minority communities around the US. But they instead worked on an election talk show that consisted of eight episodes.

“The election show is essentially your traditional show but created for digital. We talk to public figures who comment on topics that are central to the upcoming elections like healthcare, women’s rights, black lives matter and immigration, among other issues,” she shared.

Before wrapping up the conversation, Zahra shared what it has been like for her to cover the US elections. She said that it is tough for young people to be energized in this country because of polarization and party politics.

“Even though I am also exhausted by the news cycle, the election cycle and Trump vs. Biden updates that you constantly see. But as a journalist, this is my job and I have to do it,” she said.

Zahra added that the American media has become so polarized that the pieces that they are working on and the people that they are talking to are like an echo chamber.

“It is the same people that are listening and watching, who maybe agree to those viewpoints. The people who should actually be watching it are not really watching and you see this happening around the world. I do not know the answer to how we solve that but it is just something that I am thinking about, especially now that we are doing these shows,” she said signing off.

Focus

PHOTO CREDIT-CAROLINE MARTINS

Pretrial detention – the Sisyphean Misery in Egypt

By Samar Elhussieny

The Greek myth about Sisyphus embodied god's retaliation in doing the same thing over and over with no result. Everytime he climbed up the mountain with high hopes of eventually making it to the top, he was left disappointed. Doing the same thing for life with no result is a cruel punishment indeed.

What if you didn’t piss off a god, what if you just pissed off a president, a police officer, a civil servant, or a colonel - in Egypt, the punishment is almost the same. Endless Sisyphean misery under the auspices of president Adel-Fattah Al-Sisi’s regime.

There’s no definition for pre-trial detention in the Egyptian law but public prosecution defines it as one of the interrogation procedures. Until 2013, pre-trial detention was good news in Egypt. If you were a political prisoner, a journalist, or a criminal, pre-trial detention meant there is a limit for their temporary detention. Their pending status would not last long and soon they were able see a judge, present their defense, and get cleared.

Whereas, Article 143 of the criminal procedures code constitutes that detainees shall be interrogated within three months of their arrest and notified of their charges and court positions that the duration of pre-trial detention should not, anyhow, exceed one-third of the penalty and sets a long list of conditions for pre-trial detention, the public prosecution office in practice does not respect any of these conditions, particularly with prisoners of conscience.

From 2013 onwards, pre-trial detention has been used as a political punishment against journalists, political activists, human rights activists and prisoners of conscience. According to the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, the number of detainees who excessed their pre-trial detention duration was 1,464 by the end of 2016. As of May 2020, the total number of pre-trial detainees, mostly apprehended for political reasons in Egypt, ranged from 25,000 to 30,000.

My first report in The Coalition For Women In Journalism was about the pre-trial detention of journalist Noora Younes, followed by another report on Esraa Abdel Fatah. Ever since I have joined the organization, I have documented a pre-trial detention of women journalists in Egypt every often. As an Egyptian, and in some cases a friend of the detainee, my feelings vary from rage to sorrow, and even helplessness. I want this misery to end, or at least, I need to know when it will end.

Briefly, after her release from a pre-trial detention, journalist Basma Mostafa spoke with CFWIJ and informed us about her meeting with Esraa, who was detained in the same imprisonment facility. When Basma was leaving the prison, Esraa said to her, “My ultimate hope is to get acquitted in one of the cases, to know the time that I will serve and then retain my freedom back.”

When commenting about her own release Basma said, “I thank God that I am released now and can hold my daughters, and hug them again… I was just trying to do my job.”

Journalist Noora Younes also wrote about her detention.

“The truth is, I expected my detention from two years. I even weaned my daughter earlier in anticipation of this possibility…. I was prepared for the worst-case scenarios… Ironically, I knew from the other prisoners in my cell that Lina Attalah was here a few months ago,” she stated.

Lina Attalah, a journalist and winner of the ICFJ Knight International Journalism Award – who was briefly detained just two months before Noora and ironically, in the same cell – commented on the restrictions and targeting of journalism in Egypt.

“As Brecht said, In the dark times, there will be singing about dark times. Perhaps in the singing about dark times we can find ruptures….. we can hold space for those who are waiting for liberation,” she said.

What haunts me about pre-trial detention is the desperate repetitive misery during every single hearing. There is hope, frustration, rage and fear. However, hearings in front of the prosecutors could be the only way for families and lawyers to see the detainee. When I put myself in a journalist detainee’s shoe, I would want nothing but a verdict. It is my right as a human being to know how this will end, whatever the charges may be. I have the right to think about my future with a definite date about my release. I have the right to defend myself in front of a judge who is not biased or controlled by the military and security apparatuses. I should not feel like Sisyphus, who continues the same task each day, but ends up in the same spot – either in a cell or below a mountain with a rock on my back or chained behind bars.

Interview

Grace Panetta: On covering the US Elections in times of Covid-19 and Trump presidency

By Rabia Mushtaq

PHOTO CREDIT: MARIAN SILJEHØLM PHOTOGRAPHY

In anticipation of the November 3 US presidential elections and the ongoing Covid-19 outbreak in the country, The Coalition For Women In Journalism (CFWIJ) had a chat with New York based journalist Grace Panetta. Grace works as a politics reporter for Business Insider. She covers elections and voting for the publication. In this interview with CFWIJ, Grace tells us about her experience of working as a reporter covering one of the most monumental events this year, how Covid-19 impacted the process and decisions relating to the elections in the country and the way she handles reporting in the era of misinformation and disinformation. Scroll through to read the interview.

CFWIJ: How long have you been reporting for the Business Insider?

Grace: I started at the Business Insider almost two years ago as in intern/fellow during college. I have been reporting full-time for almost a year now. Shortly after I began working as a full-time reporter in December 2019, the pandemic hit. So most of my professional experience as a journalist has been during this pandemic, which has been interesting and there is nothing like it. This is also my first presidential election working as a journalist.

Tell us about your experience of covering the US elections?

In the beginning of the year in January and February, I knew it would be really hectic and busy, and it turned out that way. It was exciting but funny too during the Iowa caucuses. I wondered what a huge mistake, this will never happen again and the rest of the elections will never be that chaotic or have that many problems. But this was the story I ended up covering this whole year and things took such an interesting turn.

Elections in the United States of America are around the corner. How are you managing the information flow and developing news as a beat reporter?

It is, obviously, impossible to keep up with everything all at once because while covering election administration, there are different things happening in all the fifty states at all times with regards to the voting process. But I do try to follow everything and keep up with it as best as I can. It is really just figuring out what are some of the biggest issues and biggest problem spots. There is just so much litigation over election rules, so it is difficult sometimes to keep up with it all. It has been a challenge covering something so decentralized. But it has also been an exciting and interesting opportunity at the same time. Mainly, I get a lot of press releases about the litigation that happens and follow a lot of lawyers on Twitter. I try to keep tab on as many different things as possible and it is definitely a challenge for everyone.

Covid-19 has affected elections in the US this year. What has it been like for you in terms of reporting the election and voting activities during these unprecedented times?

With regards to the election and the voting process, it escalated really quickly during early March. Life was normal and we had Super Tuesday on March 3. Those elections mainly took place without any major problems. But then a week later, the majority of the country began shutting down, workplaces and schools went remote, and businesses were shut down. Then the first elections that were set to take place on March 10 definitely came up against that.

The first big one thrown into chaos by the pandemic was the Ohio presidential primary on March 17. There was a lot of last minute activity, with the Governor Mike DeWine trying to postpone it and make it all mail. The Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo and the public health commissioner got involved. Last minute court rulings were taking place, just a day before the voting was supposed to happen. They were actually able to shut down all the in-person voting that were supposed to take place and ended up holding almost entirely by mail, but some in-person voting.

This was the first time one wondered that this is going to be a problem through our elections. At that point, I hoped that the pandemic would be over by November, but that did not happen. It was at that moment in mid-March when I thought that this is going to be a big problem because all these presidential primaries were supposed to be happening in the next few months.

Look at it from the perspective of the voters. In March, there was so much we did not know about the virus. Now hindsight, even if things had gone differently and we had managed to get way more under control than we did, it will still affect the voting process because we don’t have a vaccine yet.it is not to the point where there is no widespread community transmission; in fact, now we are moving in the opposite direction with a possible third wave this fall. Officials really have stepped up but the pandemic, if ended up in another world with different measures that were taken at the federal level, the virus did not have to be this bad again in the fall.

According to news, it might take several days or weeks for election results to emerge because of Covid-19 and postal voting. Given that you have to be on top of all the news and updates concerning your beat, how are you strategizing your reporting?

The biggest race people are going to be worried about is the presidential race. In the US, we do not have the nationwide popular vote election, we the Electoral College system where every state gets a certain number of votes. So whichever candidate wins the most votes, wins all of the Electoral College votes. This year, we have all these states scaling up mail voting, which take longer to process than in-person votes, especially in the states that allow mail ballots to arrive after election day. There are more and more states saying that as long as the ballots are postmarked by election day, they will be counted, even if they are received afterwards. Every state does this differently and what it really means for us is that there are states like Arizona and Florida that have a lot of experience processing high levels of mail ballots. Florida, for example, we’re expecting to have a lot of results on election night; Ohio has also made a lot of changes to allow officials to process ballots early.

Overall, I do expect that we would not know the winner of the presidential race on election night. Decision desks, like the ones that we work with at decision desk HQ, are going to air on the side of caution and not call a race for the wrong candidate. But it also depends on the margin. It is mostly just about assuring the public that mail ballots take longer to process, it is okay to wait for results and it does not mean that anything is wrong. It just means that officials are working to get the count fairly and accurately.

During times when information is coming in every minute from various sources – particularly social media, how do you tackle misinformation and disinformation as a journalist?

There is so much misinformation out there — even some that is maliciously spread, a lot of which happens to be perpetuated and spread by the US president. The US election system is already decentralized and very complicated, given its rules and policies — not just from state to state but even by county within states, which is why there is so much confusion over the vote. It makes sense because our system is complicated and not always user-friendly or easy to understand. In this climate, where people are so paranoid and scared of what is happening, they can be more prone to buying into misinformation.

The most important message I have been trying to get out through my reporting and in my use of social media is telling people that mistakes do happen in election administration and are prone to happen in any system that is run by humans. Majority of the time it is not any malfeasance or fraud — it is extremely rare. Any mistakes that come up are results of sheer human error or sometimes incompetence in the worst scale of things. Things are always more complicated when a viral tweet, meant to inflame and provoke a reaction, gets across. It is important to understand some of the nuances and complexities in our system.

How have you dealt with sources in terms of your beat reporting, especially while covering the elections?

One of the really great things about covering a beat as decentralized as the election administration and so misunderstood, is that there are so many hardworking, dedicated officials and outside experts who are more than willing to share their expertise. They talk about issues that they are facing and try to deconstruct some of the problems that have come up this year, along with the nuances and quirks to the system.

I have had a very good experience with sourcing this year while covering elections administration. Obviously, it is a crazy time but it is such an important issue that I am very lucky to have so many people who are willing to talk.

How different are the elections this time around for you as a US citizen?

They could not have been more different, but it is incredible to see how things have changed in just four or five years. In 2016, we had just come out of the Obama presidency’s eight years and because Hillary Clinton was a democratic nominee, the election in many ways was a kind of referendum on her and a referendum on a third term of the Obama style agendas. It was really all about Hillary. And that is why a lot of people voted for Donald Trump. Hillary was unpopular and had a lot of controversies, which now seem very tame in comparison.

During that time, the economic circumstances were very different. The economy was doing relatively well in comparison. The nation was in a much better place, so there was more time and energy to focus on Clinton’s and Trump’s various personal scandals. This year, the entire focus is on Trump and his presidency, especially the way he has handled the pandemic; whereas Joe Biden is the one that is far more popular.

Report

Women journalists locked behind bars

In 2020, The Coalition For Women In Journalism (CFWIJ) documented various cases of threats and violence targeting women journalists. Over the course of this year, we also identified several cases where journalists found themselves vulnerable to state harassment in the form of arbitrary lawsuits, detentions, arrests, and even imprisonments. This year alone, 17 women journalists were arrested, detained and imprisoned in countries including the Philippines, Iran, Turkey, Egypt, China, Guatemala, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Only one among those jailed was released in September.

According to CFWIJ’s current data, 13 countries around the world have arbitrarily kept at least 38 women journalists behind the bars. The Middle East and North African region takes the top spot for locking up the most number of women journalists around the world, Southeast Asia comes second, while East Asia, Africa and Latin America follow suit.

In the MENA region, 28 women journalists are currently incarcerated in countries such as Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Syria, and Palestine. Iran has jailed the most number of women journalists around the world with nine locked up under arbitrary conditions in its prisons. Egypt and Saudi Arabia have imprisoned five women journalists; Turkey has jailed four, while Palestine and Syria have incarcerated at least one inside their prisons.

In the East Asian region China is the only country that has four women journalists locked behind the bars. Seven women journalists have been confined in different countries across the Southeast Asian region which includes the Philippines, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Two women journalists are serving imprisonment sentences in Africa and one is kept behind bars in Latin America’s Guatemala.

Following is a country-wise breakdown of women journalists detained and imprisoned around the world, as well as those released this year.

Incarcerated women journalists across the world

Following are the details of women journalists detained and imprisoned in different countries around the world.

Iran

Avisha Jalaledin was sentenced to five years in jail and has been kept behind bars since February 2018. She was arrested for peaceful participation in a protest by members of the persecuted minority in Tehran, which turned violent when security forces used water cannons, firearms, and tear gas to disperse the crowds. Avisha worked for a Sufi community news website Majzooban Noor.

Hengameh Shahidi is serving a seven-and-a-half-year prison sentence. She was arrested for “criticizing Judiciary Chief Sadegh Larijani” in December 2018, after which the court sentenced her to 12 years and nine months in prison.

Marzieh Amiri was arrested in May 2019. She worked as a reporter for a pro-reform daily Sharq. Marzieh was prosecuted for reporting about a workers' rally on International Workers' Day in Tehran. She was sentenced to ten and a half years in jail and 147 lashes by an Islamic Revolutionary Court.

Zoreh Sarve was arrested in March 2020. She was charged for “insulting the founder of the regime", "propaganda against the regime" and "meetings and conspiracy against national security". Zoreh was sentenced to three years and read the interpretation of a surah from the Quran.

Sepideh Qoliyan has been imprisoned since June 21, 2020. She reported to prison and began serving her sentence after being issued a five-year jail sentence for covering a rally by the Haft Tappeh sugar mill workers for unpaid wages. Sepideh was arrested in November 2018 in Shush for reporting the rally. She was released on bail on February 9, 2020. But returned to jail to begin her sentence.

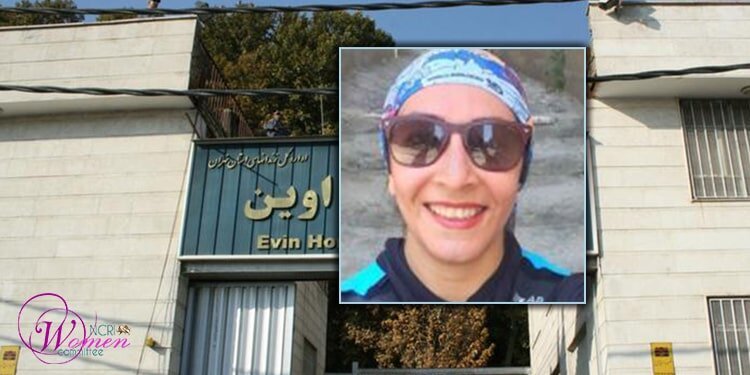

Nada Sabouri, an Iranian freelance sports reporter, started her three and a half year jail term at Tehran’s Evin prison on August 7 this year. Her imprisonment officially began five years after she was originally sentenced on charges of “assembly and collusion” after she accompanied the families of political prisoners during a protest in 2014.

Shabnam Ashaouri, editor of an economic bi-monthly Aghahinameh, was arrested on October 4. She was taken into custody by the Revolutionary Guard intelligence officers after they raided her home.

Iranian photojournalist Alieh Motalebzadeh was returned to prison on October 11, to start serving a three-year prison sentence for “meeting and conspiring against national security.” She was sentenced by the Sentence Executive Bureau of Tehran’s Evin prison, which issued the ruling against her.

On 11 October, Roghieh (Ashraf) Nafari — a student and citizen-journalist — was sent to prison after the court sentenced her to three-months of imprisonment for “anti-government propaganda”. She was persecuted for her social media posts that were rendered inaccessible after which she was arrested by security police on March 26. Her sentence was originally four-months long, but was reduced to three months after an appeal extended to the Tehran revolutionary court.

Saudi Arabia

Nouf Abdulaziz Al Jerawi was detained by Saudi authorities on June 10, 2018. She was taken into custody for her support to Lojain Al-Hathloul, Eman Al-Nafajan, and Aziza Al-Yousef, all of whom protested against the ban on driving of women with charges of “being an enemy of the state”.

Nassima al-Sada remains detained since July 2018 without any charges or trial. She was placed in solitary confinement since early February in 2019, at the Al-Mabahith prison in Dammam.

Maha Al-Rafidi was arrested during a crackdown against activists, journalists and writers across the Kingdom on September 28, 2019. She has been kept behind bars without being sentenced since then.

Zana Al-Shahri was arrested in September 2019, after the Saudi authorities went on a spree to arrest and detain dissidents, journalists and human rights defenders. There has been no update about Zana’s fate ever since she was taken into custody.

Loujain Al-Hathloul was detained in May 2018, and has been kept behind bars by Saudi authorities. She was taken into custody for her activism related to women’s rights and human rights abuses across the kingdom.

Egypt

Esraa Abdel Fatah was arrested in October 2019. She was taken into custody in a series of arrests targeting human rights defenders, journalists, and activists after they took to the streets against el-Sisi’s regime and his luxurious lifestyle. Authorities continue to renew her detention by using coronavirus and other legal tactics as excuses to keep her confined.

Solafa Magdy has been in prison since November 2019. She, along with her husband and a lawyer, are facing charges of joining a "terrorist group", after they were detained amid a string of similar arrests in 2019. Her sentence is not yet served.

Shaima Sami, a journalist and former researcher for the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, was arrested from her home in Alexandria by the Egyptian security forces in May 2020 Her arrest came several days after other journalists in the country have also been detained and arrested for reporting on Covid-19. She has since been incarcerated with no signs of freedom in sight.

Sanaa Seif was detained on June 23. She was protesting outside the prosecutor's office, after which she was forced into a minivan and escorted to the national security prosecution office. She was interrogated for inciting protests and spreading rumors of health conditions due to COVID-19. However, the authorities did not release her.

Doaa Khalifa was arbitrarily arrested by Egyptian authorities and was thrown into the Al-Qantar prison without interrogation. Her detention renewed without being questioned or moved to court.

Turkey

Hatice Duman was arrested in July 2003. She was sentenced to life imprisonment for “managing a terrorist organization”. She appealed her case to the Court of Cassation in 2012, which was rejected.

Hanım Büşra Erdal has been behind bars since July 2016. She was sentenced to six years and three months imprisonment for being a member of an armed terrorist organization.

Ayşenur Parıldak was sent to prison in August 2016. She was arrested on charges of “membership of a terrorist organization” and was sentenced to seven and a half years in prison.

Müyesser Yıldız was detained alongside TELE1 TV Ankara Representative İsmail Dükel on June 8, by Ankara Counter-Terrorism Branch of the State Police Department.

China

Journalist Gulmira Imin was arrested on charges of “Splittism, leaking state secrets, and organizing an illegal demonstration” in July 2009. She participated in a major demonstration protesting the deaths of Uighur migrant workers in Guangdong Province on July 5. Gulmira was taken into custody on July 14, after authorities alleged she had organized the protests. The court sentenced her to life imprisonment.

Atikem Rozi has been in prison since February 2014. She was detained at an undisclosed location in Xinjiang on charges of participating in alleged separatist activities led by Ilham Tohti, founder of the Xinjiang news website Uighurbiz.

Wang Shurong has been behind bars for three years and 10 months. She had been volunteering for several years as a citizen journalist with the website 64 Tianwang Human Rights Center when she was detained in February 2016.

On June 22, the family of Zhang Zhan — a citizen journalist based in Shanghai — was informed about her arrest after she was initially detained for her coronavirus reporting in May for her social media posts detailing the state of Covid-19 outbreak in China’s Wuhan city. She was earlier held by the police in the municipality’s Pudong district on “public disturbance charges” and remains detained in Shanghai. In October, CFWIJ found out about Zhang’s deteriorating health conditions after she went on strike to protest against her arbitrary arrest.

Burundi

Two women journalists from Burundi remain imprisoned after they were first detained while on a reporting assignment in October 2019. Both Agnès Ndirubusa and Christine Kamikazi were arrested in December 2019. They were eventually sentenced to two and a half years in prison and a fine of one million Burundian francs for “trying to undermine state security” in January this year.

Vietnam

Huynh Thuc Vy was sentenced in November 2018 to two years and nine months in prison on charges of defacing the country’s national flag.

Prominent human rights campaigner and writer Pham Doan Trang was arrested by the Vietnamese authorities on October 6, from her home in Ho Chi Minh City. She was charged for “conducting anti-state propaganda”, an offence that can land her inside the prison for as long as 20 years.

Cambodia

Two women journalists Long Kunthea and Phuon Keoreaksmey, and their male colleague Thon Ratha, all of whom work for the environmental website Mother Nature Cambodia, were arrested on September 3. They were placed in pre-trial detention three days later on a charge of “incitement to commit a felony or cause social unrest.” On October 20, a judge at the Appeal Court denied requests to drop their cases or grant bail, after which the journalists remain imprisoned till date.

Palestine

Bushra Al-Tawil was arrested from her house and on 16 December 2019, the Israeli Army Commander of the Central Command issued a military order to put her in administrative detention for four months with no set charges, on May 2020 her detention was extended yet again.

Syria

Tal al-Mallouhi was arrested in December 2009. On February 14, 2011, the State Security Court in Damascus convicted Al-Mallouhi of “divulging information to a foreign state.”

Philippines

Filipino journalist Frenchimae Cumpio was arrested along with four human rights activists on February 6, 2020. She was taken into custody during simultaneous raids across the Tacloban city targeting journalists and human rights activists. She remains in pretrial detention till date.

Laos

Houayheuang Xayabouly was arrested in September 2019. She posted a video on Facebook that drew attention to the government’s negligence towards the devastating floods in Champasak and Salavan. Houayheuang has been jailed on charges of “spreading propaganda against the Lao People's Democratic Republic” and “trying to overthrow the Party, state and government”. She was sentenced to five years of imprisonment and a fine of 20 million kip.

Guatemala

In the Latin American country Guatemala, Anastasia Mejía Tiriquiz — the director of the radio station Xol Abaj Radio and Xol Abaj TV — was arrested by the Guatemalan National Civil Police (PNC) in Joyabaj on September 21. She was accused on charges of “sedition, attack with specific aggravations, aggravated arson and aggravated robbery”. Anastasia was taken into custody after she documented cases of corruption by the Quiché municipal authorities.

Women journalists acquitted this year

Six women journalists, who were arrested on different occasions and in different countries, were released this year. Following are the details of their arrests and release.

A few weeks ago on October 7, Narges Mohammadi — an Iranian journalist and human rights activist — was released from Zanjan prison in the wake of a reduced sentence. After serving more than eight years of her prison sentence, Narges was eventually freed following urgent calls for her release due to her pre-existing health issues and possible COVID-19 symptoms. Narges was sentenced to 16 years of imprisonment on several counts including for “membership in the [now banned] Step by Step to Stop the Death Penalty” group by the Revolutionary Court of Iran in May 2016. She was locked behind bars for her work since May 2015.

Turkish journalist Hülya Kılınç was acquitted in terms of TCK 329, but was sentenced to three years and nine months in prison for "publishing information and documents regarding the duties and activities of the National Intelligence Organization through the press and media". Considering the time spent in prison, the journalist was released in September this year. Hülya was arrested in March 2020 and was sued for her news article about an MIT (Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization) member who died in Libya.

Chimengul Awut, a Chinese Uighur journalist, was released on August 14 this year. She was arrested and sent to a re-education camp for her involvement in editing a novel that the Chinese government took issue with.

Sepideh Moradi, an Iranian journalist and Sufi, was released on February 8 this year. She was arrested after being subjected to physical assault during a protest gathering of Gonabadi Dervishes in Tehran’s Golestan-e Haftom Avenue, which took place on February 19 and 20 in 2018. Sepideh was imprisoned in the Qarchak Prison of Varamin and was later transferred to the Women’s Ward of Evin Prison in Tehran.

Li Zhaoxiu, a Chinese volunteer journalist for the independent human rights news website 64 Tianwang, was released on February 10, 2020. She was arrested by the Chengdu police in September 2017. She was sentenced to two years and six months in prison on charges of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles” in August 2019.

In January this year, Vietnamese journalist Trần Thị Nga was released, after which she left the country to live in exile. She was serving a nine year prison sentence, which was due to be followed by a five year probation period. Tran, along with her husband, was arrested at their home in Phủ Lý in Ha Nam Province on January 21, 2017. She was charged for “using the internet to spread some propaganda videos and writings that are against the government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.”

Round Up Of Threats Women Journalists Faced

Iraq: Arrest warrant issued for journalist Suadad Al-Salhy over a libel lawsuit.

An arrest warrant for Middle East Eye reporter Suadad Al-Salhy was issued concerning a libel lawsuit.

Oct 23, 2020

Ireland: Defamation lawsuit against Dublin Inquirer’s journalists is a waste of time and resources

On August 31, Dublin Inquirer’s co-founder Sam Tranum and its reporter Laoise Neylon were served with summons about a defamation lawsuit filed against them for an article.

Oct 23, 2020

Greece: German documentary journalists arbitrarily detained in Samos island

On 19 October 2020, a German media crew making a documentary about climate-induced migration on the Greek island of Samos were detained for seven hours.

Oct 23, 2020

Croatia: N1 TV crew verbally harassed during Covid-19 interview

The N1 TV crew was getting ready for the live broadcast in a public green area when a couple approached them and made comments about the crew not wearing masks.

Oct 23, 2020

Kuwait: TV presenter Sazdell El-Kak deported over claims of immoral social media content and violating public decency law.

V presenter Sazdell deported from Kuwait over claims of violating dress code conduct and posting so called immoral social media content.

Oct 22, 2020

Algeria: Journalist Hadda Hezam sued over allegations of defaming Islam.

Al-Shorouk media sues journalist and editor-in-chief of Al-Fagr news outlet, Hadda Hezam over allegations of defaming and attacking Islam.

Oct 22, 2020

Turkey: Sabiha Temizkan sentenced to one year three months imprisonment over her social media post six years ago

Verdict hearing on the case against journalist Sabiha Temizkan over charges of “spreading terror propaganda” was held.

Oct 22, 2020

United States: President Trump continues attacking women journalists. Now Kristen Welker is under his radar through a smear campaign

President Donald Trump who is notorious for his treatment of journalists launched a smear campaign against award winning journalist Kristen Welker who will moderate the debate.

Oct 21, 2020

Egypt: Journalist Doaa Khalifa went missing for three weeks and was found arbitrarily detained in an Egyptian prison.

Journalist Doaa Khalifa found arbitrarily detained in Egypt pending case no.880\2020 after being missing for three weeks.

Oct 20, 2020

United States: Local journalist fired for speaking out against exploitation of labor

Floyd Press managing editor Ashley Spinks was fired from her job last week after she gave an interview about her working conditions to Radio IQ.

Oct 19, 2020

Congo: Journalist Rozenn Kalafulo forced into hiding due to threats from the military

Congolese journalist Rozenn Kalafulo said in an interview she gave to AFP that she has been hiding in an unknown destination for a week after threatening.

Oct 16, 2020

South Africa: Two women journalists attacked while covering protests by farmers

The Citizen newspaper’s photographer Tracy Lee Stark and reporter Marizka Coetzer were attacked and impeded at work.

Oct 16, 2020

Spain: Journalist attacked, harassed and impeded at work while covering pro-independence protests

Mayka Navarro was at the protests scene on Friday, covering the protests for The Ana Rosa Program when a group of protesters surrounded Mayka, yelling at her and hitting her with a flag pole.

Oct 14, 2020

Belarus: Police violence towards members of the press continues with arrest of 40 journalists

Since the beginning of the year, the Belarusian Association of Journalists has recorded more than 400 cases of harassment of journalists for their professional activities.

Oct 14, 2020

Yemen: Online harassment campaigns resulted in the abduction attempt of journalist Weaam Alsofy’s son by Al-Houthi group affiliated members.

Abduction attempt of Journalist Weam Al-Sofy’s son following online smear campaigns against Weaam Alsofy is proof that online harassment has severe offline consequences.

Oct 13, 2020

Pakistan: Defamation laws misused to attack freedom of speech. Journalist Maham Javaid booked for exposing sexual misconduct of Pakistani celebrity

The Coalition For Women In Journalism (CFWIJ) condemns the unjustified lawsuit filed against journalist Maham Javaid.

Oct 12, 2020

Guatemala: Indigenous journalist Anastasia Mejía is arrested without hearing over her reporting on anti-corruption protests

Xol Abaj radio reporter and indigenous rights activist Anastasia Mejia was arrested with charges of “sedition”, “aggravated attack”, and “arson”.

Oct 12, 2020

Turkey: Journalists from Jinnews and Mesopotamia Agency arrested for reporting on an inhumane torture committed by the military

Jinnews reporter Sehriban Abi, journalist Nazan Sala and Mesopotamia Agency correspondents Adnan Bilen and Cemil Ugur got arrested.

Oct 9, 2020

Germany: Police evicts anarcha queer feminist squat and impedes journalists at work

Liebig34, an “anarcho-queer-feminist” housing project in Berlin, has been cleared of residents following a contentious eviction involving around 1,500 police officers.

Oct 9, 2020

Belarus: Seven women journalists detained, three remain under custody for reporting protests

16 journalists were detained in Belarus, seven of them being women.

Oct 8, 2020

Saudi Arabia: Journalist Ghada Oueiss is once again attacked by accounts suspected to be tied to the Saudi government

Journalist Ghada Oueiss was targeted by online attacks, for the second time in less than 2 months by Saudi government-linked accounts over her dissident views.

Oct 7, 2020

Vietnam: Leading democracy activist and award winning journalist Pham Doan Trang arrested

RSF’s 2019 Press Freedom Prize winner journalist turned activist Pham Doan Trang was arrested today during a raid at her house.

Oct 7, 2020

China: Citizen journalist Zhang Zhan is in hunger strike due to her unlawful imprisonment

We are severely worried about the health of citizen journalist Zhang Zhan, who is the only woman journalist who remains under bars.

Oct 5, 2020

India: Principle of “journalists cannot be forced to expose their sources” breached by the state

Large scale protests have erupted last week to protest the brutal gang rape and murder of a Dalit woman by upper-caste men in Hathras.

Oct 5, 2020

Egypt: Journalism deemed a crime. Journalist Basma Mostafa abducted and detained for covering a story.

Journalist Basma Mostafa was abducted and later detained for covering the murder of a citizen in the Luxor Governorate at the hands of a national security officer.

Oct 5, 2020

Iran: Nada Sabouri started her jail sentence of 3.5 years over 2014 conviction

Nada Sabouri was taken to Evin prison to serve a sentence of three and a half years in prison.

Oct 5, 2020

Nigeria: Journalist attacked by park manager official in front of her kids

Zainab Olayiwola, female journalist at a private radio station named Jamz FM, and her kids were attacked by park manager officials while boarding a tricycle on October 4.

Oct 4, 2020

Libya: Journalist Karima Nagy’s accreditation was revoked. CFWIJ is concerned about the safety of women journalists.

Tunisian journalist Kareema Nagy’s accreditation got revoked in Libya over allegations of espionage by the intelligence agency.

Oct 3, 2020

Russia: Irina Slavina deserves justice. We are devastated at her death caused due to state oppression.

CFWIJ is devastated at the death of Russian journalist Irina Slavina, who passed away after setting herself on fire to protest an unjustified raid at her apartment a day earlier.

Oct 3, 2020

Slovenia: Necenzurirano manager is “SLAPP”ed with 13 different lawsuits for reporting on fraud of “tax expert”

News portal Necenzurirano.si’s managers are facing a total of 39 law cases initiated against them due to “defamation” of a famous tax expert.

Oct 2, 2020

Women Journalists To Follow

Jane Lytvynenko

Toronto-based Jane Lytvynenko is a senior reporter for Buzzfeed News covering disinformation and online investigations. You’ll usually find her busting all the disinformation you find floating online and get you all the factual information you ought to follow, especially during these very crucial times.

Catherine Kim

Based in New York City, Catherine Kim is the Global Head of Digital News at NBC News and MSNBC. She is at the helm of content, editorial strategy, publishing and social for the network’s news content covering everything from politics to diversity. You’ll find her tweeting about the US elections and often busting fake news on her Twitter.

Briana K. Stewart

Briana Stewart is a New York based News Campaign reporter and is covering the U.S. presidential elections for ABC. Her focus on reporting the elections as a woman of color reflects in her work. From the significance of race during this monumental event to her timely updates on Twitter, Briana does it all too well.

Badass Women Authors

Everything Is Figureoutable

Written by Marie Forleo, the host of the award-winning MarieTV and The Marie Forleo Podcast, this book serves as a guide to help you become a creative force. It will wire your brain to function more positively and creatively no matter how difficult the situation might seem. Deemed by many as a must-read for anyone aiming to challenge their fears and make their dreams come true, the book will convince you to believe in the idea of figuring everything out.

Buy Yourself the F*cking Lilies: And Other Rituals to Fix Your Life, from Someone Who's Been There

Tara Schuster, an accomplished entertainment executive and playwright, brings us this gem focused on teaching us the importance of self-love. Through her book, she shares the simple, everyday rituals that helped her transform her life. It teaches you how to be grateful even if you’re not experiencing the feelings of gratitude, dig for your emotional traumas and gradually work to heal them, stop limiting and criticizing yourself and start live on your own terms.

The Wrong Kind of Woman

This book, penned by Sarah McCraw Crow, revolves around the '70s-era second-wave feminist movement. It focuses on the life of Virginia, a woman who suddenly lost her professor husband to death. She later finds herself observing four unmarried women who are disdained while working at a college, which is otherwise male-dominated. In the midst of incessant threats and resistance, she stands with them to bring the women's movement to Clarendon College.

Untamed

Glennon Doyle explores the joy and peace that one finds in listening to one’s own voice. In this intimate memoir, she uses a voice that resonant to most women who strive to be good while performing the different roles throughout their life. But how this striving leaves them overwhelmed, disappointed, weary and stagnant is something you’d find Doyle emphasizing on in her book.

Podcast Picks

Can He Do That?

Hosted by Washington Post’s Allison Michaels, this podcast is your best bet to understand the powers that an American president holds. For this podcast Allison speaks with Post reporters with focus on the powers and limits within which the American president runs his office. The show is currently focused on elections, the politics surrounding this crucial event and what the future holds.

Listen here.

Politically Sound

Everyday, Politically Sound gives you access to the best scoop on American politics and ongoing discussion about the elections. What’s happening in the day to day political arena to election-focused content explained in-depth encompassing its various themes, this podcast hosted by Nia-Malika Henderson and David Chalian is all you need to stay informed.

Listen here.

In the Thick

Politics can never be separated from race and this podcast is a testament to this belief. In The Thick gives you a chance to observe politics through the lens of identity and race. As people of color, hosts Maria Hinojosa and Julio Ricardo Varela discuss issues related to racial justice, which are often overlooked or played down. They initiate conversations that crucial particularly in present times.

Listen here.

The Brown Girls Guide to Politics

A’shanti F. Gholar, the founder and host of The Brown Girls Guide to Politics, brings political conversation for women of color through her podcast. From interviews to contemporary discussions, the podcast serves as a resource for women of color who want to dive deep into and analyze the world of politics.

Listen here.