United Kingdom: Safety of Journalists - Gender Perspective

This is the original document of submission by the Coalition For Women In Journalism, to the call for submission for Safety Of Journalists by the United Kingdom Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Home Office.

The Coalition for Women in Journalism (CFWIJ) fosters and supports camaraderie between women journalists around the globe. We were the first to pioneer a worldwide support network for women journalists and the first to launch a global advocacy for press freedom focused on women journalists. In that we monitor safety and press freedom for women journalists from 92 counties, and the United Kingdom has been one of the key focuses. In this submission we will prioritise threats and issues faced by women across the U.K, with a brief additional input on how the media environment affects all journalists and media workers.

This submission will focus on:

General Trends and Types of Media Freedom Violations Targeting Women

As seen in a number of European countries, the state of media freedom in the UK is on perilous footing, with the frequency and severity of threats facing journalists and media workers increasing. However, for women in journalism the situation is even more complex. While having to endure the same threats their male colleagues face, such as the increased discrediting of journalism, as ‘fake news’ or propaganda, threats of physical retribution for coverage, increased dangers from reporting in the field, alongside other threats, women also have to endure specifically gendered threats that emerge solely from their gender and their position in journalism, as well as the broader society. Reporters Without Borders (RSF), in their recent report, Sexism’s Toll on Journalism stated that ‘women journalists endure “twice the danger” of their male colleagues because of the risk of sexist violence both in the field and in their own newsrooms.’

Overview

Since the beginning of 2018, the Council of Europe Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and Safety of Journalists recorded 28 alerts for media freedom violations in the United Kingdom. In the same period, according to Mapping Media Freedom, a platform that brings together verified reports of media freedom violations managed by the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF), 84 alerts were published on the platform documenting media freedom violations in the UK. Where the identity and gender of the threatened journalist and media worker is known, at least 27 involved women as the target.

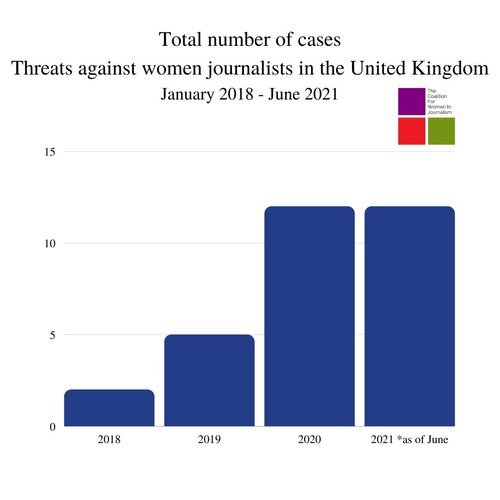

The CFWIJ’s own analysis demonstrates a concerning upward trend in the UK. For example, in the entire year of 2020, CFWIJ documented 12 violations against women journalists. In 2021, this number was reached halfway through the year. Of the 12 cases, 8 were instances of abuse and threats both in physical and digital spaces.

This is within a broader European context that demonstrates similar failings. Europe has become one of the most dangerous regions for journalists arounds the world. CFWIJ documented 75 cases of violence and threats against women journalists across Europe between 1 January and 30 June 2021. 14.5% of the violations against women reporters around the world were documented in this region in the first half of 2021. Considering the violence against women in media, Europe is the third most dangerous region around the world, as of July 2021.

In the United Kingdom in particular, the range of incidents demonstrates the complex and challenging environment within which journalists are expected to work. Of the 27 Mapping Media Freedom alerts outlined above involving women, 19 of them included threats of intimidation or threats of violence aimed at the journalist, with a number of other incidents involving the trolling, harassment and bullying of women. This was carried out by a number of means, including online harassment and organised smear campaigns, altercations in public locations, graffiti threats of gun violence and threats against the journalist’s home life or family. As many of these incidents took place online or in public locations, such as the streets and parks (College Green outside the Palace of Westminster in London is the location of two alerts) a significant number of the alerts (13 out of the 27) were carried out by unknown members of the public, such as protesters, with a further nine alerts coming from an unknown source. While there are many disparate causes for each violation, a virulent and growing anti-media sentiment, which captures a wide spectrum of views, from discrediting journalistic work and alleging falsehoods or the peddling of ‘fake news’ to the threatened of physical or sexual violence against journalists solely for their work can be seen in many of the threats coming from known and unknown members of the public. Increasingly, this sentiment has shaped, and is continuing to shape, the media landscape across the UK and has been felt disproportionately by women.

This does not come out of nowhere. In fact, while it has animated public sentiment towards the press, it has been ennobled by statements or actions made by state entities and politicians which have demonised, targeted or harassed journalists and media workers. While prominent in countries such as the US, India, The Philippines, Slovenia, Poland and a number of others, the UK is not immune. A prominent example of this were the online comments made by UK Treasury & Equalities Minister, Kemi Badenoch MP aimed at Nadine White, a former journalist for Huffington Post UK. The minister discredited the journalist’s reporting, alleging she had falsified her reporting, and refused to apologise or remove the message after leading media outlets, press freedom organisations and other MPs condemned the incident. The minister’s actions opened up Ms White to a torrent of online abuse from pseudonymous accounts and highlights how the normalisation of media freedom violations has been strengthened by high-level involvement, who may see the discrediting of critical reporting, as a legitimate public relations strategy. The impact of this form of interference from policy makers cannot be underplayed. For instance, in July 2021, it was reported by the Financial Times that the appointment of former Huffington Post UK Editor-in-Chief, Jess Brammar to a senior editorial post at the BBC was blocked due to interference by Sir Robbie Gibb, a non-executive director at the corporation with ties to the government (he was formerly Theresa May’s communications director during her tenure as prime minister). In a text exchange with the BBC’s director for news and current affairs, Fran Unsworth, Sir Gibb told her that she “cannot make this appointment” and that the government’s “fragile trust in the BBC will be shattered” if she went ahead. According to the Financial Times, “[o]ne person involved in the appointment process said some of Gibb’s concerns relate to Brammar’s handling of a dispute with Treasury minister Kemi Bandenoch last year.” While this form of intervention harms public trust in the BBC, and the government’s relationship to the broadcaster, it also chills editors’ and senior staff’s willingness to advocate on behalf of, and protect their staff.

Threats and harassment are broadly framed around verbal or typed aggression that could suggest potential physical harm, or breed a sense of isolation or fear within the journalist that may make them uncomfortable or unwilling to continue their work. While this will be explored in a later section, this dynamic is central to the media environment for women in journalism, across the UK and should not be discounted solely because many threats may not include the realisation of physical threats. In the years that led up to the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia in Malta, she endured years of online abuse and threats, alongside a number of other threats including the poisoning of her family pet and an arson attack on her home.

On 18 April 2019, journalist Lyra McKee was shot while covering a riot in Derry, Northern Ireland. While the ‘New IRA’ claimed responsibility and a number of people have been arrested and someone has been charged with her murder, over two years later no convictions have been made. This follows the 2001 murder of Sunday World journalist Martin O’Hagan, which remains unsolved nearly 20 years later. Without an effective and timely justice system that holds those attacking journalists to account, impunity will continue to embolden those who seek to silence journalists. The increase in threats against journalists in Northern Ireland, which include blanket threats against two newspapers, online smear campaigns against women and their children and threatening graffiti demonstrates the fragility of the media environment where crimes are not prosecuted and protections are inadequate.

Online Harassment, Threats and Smear Campaign

While the internet has become an invaluable tool for journalists and media workers to carry out their work, it has also enabled harassment, threats and organised smear campaigns to be directed at journalists in a manner that appears to escape all conventional protection regimes. This has become so entrenched that it has been incorporated into the assumed risks that come with carrying out journalistic functions. This normalisation, while threatening the safety and wellbeing of journalists, also ensures that all monitoring and reporting of the trend are woefully inadequate as many journalists may not identify or report threats as they are taken to be ‘part of the job.’ As highlighted by the National Union of Journalists in their 2018 submission to the Women and Equality Committee, this issue is strengthened when work is precarious: ‘There is a particular problem when the workforce is casualised. People fear that raising a complaint without the security of a staff contract will damage their future employment prospects.’

According to a recent study by UNESCO, which analysed results of a survey of 900 journalists and media workers in 125 countries, ‘nearly three quarters of the respondents who identified as women (73%) reported receiving online abuse, with 26% saying it had impacted their mental health.’ A similar 2018 study by Trollbusters and the International Women’s Media Foundation in 2018 found that 63 percent of respondents indicated they had been threatened or harassed online and one in 10 respondents had experienced a death threat in the past year. On a more granular level, looking at specific outlets, The Guardian ‘commissioned research into the 70m comments left on its site since 2006 and discovered that of the 10 most abused writers eight are women.’ The dynamics of online harassment are oftentimes specific to individual cases, but abuse through social media accounts and professional and personal email addresses is common. A number of journalists have reported spikes of abuse around the publication of reporting on a wide range of sensitive topics including organised crime, the UK’s exit from the European Union, issues around migration and protections for refugees, responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, mainstream political organising and conspiracy theories.

However, the type of coverage that invites online harassment is diverse and not isolated to sensitive political or social issues. For example, BBC reporter Sonja McLaughlan covered the

Wales v England Six Nations rugby match that took place on Saturday 27 February 2021. Due to unsubstantiated claims that she was biased to one team over the other, she received significant online abuse. While both teams, the Six Nations tournament and the BBC made statements in support, this demonstrates the wide reach of online abuse that affects women in every aspect of journalism. Sexualised and gendered harassment against women sports journalists however, is not restricted to online spaces alone. This year, senior football correspondent for The Independent, Melissa Reddy came forward with testimony from covering a 2016 league cup football match where she was interrupted by an unwanted kiss from a fan before another man exposed himself to her, again as she was recording.

As part of her recounting the experience, she wrote:

I do not want to admit I’m shaken. I pack up, make sure they have gone far enough away and then walk the 50 or so steps into the hotel. I send my manager a WhatsApp, explaining why no video will be forthcoming tonight. He is aghast at what has happened, but I tell him it’s “just one of those”.

Irrespective of the types of journalism targeted, there is a common approach, which the CFWIJ has defined as the “shoot the messenger” form of abuse, which targets the journalist, as the conveyer of the information, irrespective of the topic. This is highlighted by the online harassment and trolling aimed at the radio journalist, Natalie Higgins, which has been gendered and misogynistic in nature, with a number of online users suggesting that "she's too ugly to get raped” and so should not have to worry about sexual assault. According to CFWIJ’s reporting on this case: “Natalie believes she is an easy target for people who are unhappy with the news cycle or certain political developments. She consequently becomes a casualty of the shoot-the-messenger approach employed by online trolls.” Ms Higgins is a young journalist and the threats she has faced raises concerns that if women who are new to the industry receive abuse solely for carrying out their work it could encourage many to step away from the industry and many others to not enter it in the first instance.

Other journalists report a more generalised atmosphere of abuse that is random, enduring and ongoing throughout the year. Speaking to the Media Diversity Institute, Marianna Spring, the BBC’s Disinformation reporter has stated that: “I would say there’s a committed minority of people who bombard me with abuse - on average between one and 12 messages a day”. She also reported that the amount of abuse increases after she publishes her work. Due to the nature of her reporting, which includes conspiracy theories, a significant amount of abuse she receives is gendered and misogynistic in nature, as well as allegations of paedophilia, child abuse, and being part of a 'globalist' conspiracy. She has also received explicit threats including "I certainly hope you get what's coming to you" and "watch when you are seen in public".

Online harassment is not always isolated to the journalists themselves and a number of cases demonstrate the targeting of journalists’ families as an abusive strategy to threaten reporters into silence. In the later section, the threats of sexual violence aimed at the infant son of Patricia Devlin in Northern Ireland are expanded on in more detail. In a similar case, Camilla Tominey, award-winning journalist and associate editor for The Telegraph received online death threats via email to her website, which targeted the journalist and her children due to her reporting on the Royal Family. Threats against family members, especially young children, are disproportionately used to target women and shows the importance of support offerings being designed to support not just the journalist themselves, but their family.

Any response to online harassment and threats needs to be able to diagnose and identify the different trends, motivations and mechanisms by which this harassment is propagated. Harassment can be organic and decentralised, with individuals taking to online platforms to target journalists and media workers. This can be recurrent, returning whenever the journalist publishes their reporting or when they speak up on social media, or a solitary threat that is not repeated or followed up on. Beyond this, smear campaigns are more coordinated attacks that may include numerous different individuals flooding the journalist with abuse. They may reuse topics, wording or hashtags in an attempt to falsify the sense of a ‘harmed’ community speaking out against alleged falsehoods or attacks propagated by the journalist or media worker. While many of the accounts may have small follower accounts and take on pseudonymous naming conventions, smear campaigns often gain traction by being amplified by large and prominent users who while, avoiding explicit threats or calls to action, can encourage their followers to disregard that care and directly threaten the journalist or media worker. This coordination can take place across a number of different platforms making platform-specific protection mechanisms of limited efficacy. For example, while the journalist may face concerted harassment on twitter or facebook, the participants in the smear campaign may use other platforms such as Reddit, or specific chat rooms, to plan and coordinate the abuse.

This blurring of online and offline threats is central to the nature of online harassment. While online harassment is severe enough in of itself, oftentimes encouraging journalists to step back from important issues or from journalism altogether, the escalation into offline threats including physical attacks must be proactively protected against. In May 2020, Chief reporter at The Mail in Barrow, Amy Fenton was advised by the police to leave her home due to credible threats made against her due to her reporting on an ongoing court case. Threats of sexual violence were made against her online, while her colleagues were also harassed, online and off. This demonstrated the dangers of escalation, as well as the importance of proactive policing. However, a more holistic approach is required to ensure journalists are protected. While the police service recommended that she, and her child, should leave their home, they were unable to offer a structured protection regime, which included housing. This is vital as it cannot be assumed that journalists are able to organise and fund alternative living arrangements, oftentimes with children or other caring responsibilities, for an unknown amount of time.

Online harassment cannot be tackled without identifying these different modes of abuse as each would require tailored and specific responses. The actions of prominent users with significant online followers or broader significance (i.e. a politician or media personality) is central to the diffusion of online harassment, even outside organised smear campaigns, as their statements or messages can encourage others to follow suit even if not requested or foreseen. In the example outlined above, where Kemi Badenoch MP targeted a journalist due to their reporting, her seniority as a minister gave the abuse the visage of respectability which was itself reinforced by the minister’s resistance to apologise or delete the derogatory series of messages. This encouraged further abuse aimed at the journalist even though there was no known encouragement from the minister. A similar example can be seen in the targeting of Observer journalist Carole Cadwalladr due to her reporting on data misuse by one of the campaigns calling on the UK to leave the EU. Campaign donor, Aaron Banks tweeted “@carolecadwalla wouldn’t be so lippy in Russia!” and the official twitter account for Leave.EU tweeted a video, headlined: '@carolecadwalla takes a hit as the Russian conspiracy deepens.' According to Cadwalladr’s own words: ‘It described me as “hysterical Guardian investigator Carole Codswallop”'. The video was a clip of the film Airplane! and they had photoshopped my face into that of a hysterical woman being hit repeatedly around the head. The last frame showed a woman with a gun. In the background, the Russian anthem played.’ This was against a backdrop of the Russian state also targeting the journalist, referring to her and other critical journalists, when “calling on the unscrupulous journalists and politicians: stop imposing this fake agenda.” When influence state and non-state actors target journalists and media workers with few repercussions, it emboldens others to continue to amplify and continue the strategy of abuse.

Potential Remedies

A central difficulty when addressing the cause of online harassment is the diffuse set of actors involved in hosting or propagating online harassment. While states have a responsibility to ensure all laws that protect journalists are up-to-date, relevant and enforceable (while also protecting the broader right to free expression), online harassment also requires proportionate and necessary engagement from the platforms who host the harassment, which are global in nature and oftentimes headquartered offshore (generally the US). This is a global and growing issue, and one that cannot be covered in significant detail here. However, it is important to state that any policy by which journalists can be protected from online threats cannot ignore the diverse motivations of the different actors involved and the resultant need for multilateral, nuanced and meaningful engagement on this important issue.

The central approach taken by the state to protect women in journalism will frame all its subsequent action. As outlined by a report commissioned by the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media on the safety of female journalists online, states should deploy a gender-responsive approach, which includes: departing from an understanding of the diverse conditions that influence the work and life of men and women of different groups in society; actively produce disaggregated data and information; ensure participatory and multi-stakeholder processes; properly resource, plan and evaluate the work that is needed; and make sure that measures aimed at protecting women journalists do not undermine their fundamental rights.

While online threats can set the foundations for offline threats, including acts of physical or gendered violence, online harassment and threats should not be seen as a harmless route to harm. Identifying online threats as threats in themselves, while at the same time potentially the early warning signs for potential escalation, is central to ensuring they are treated with the severity they require. It is also important to challenge the normalisation of these kinds of threats to ensure they are not endured as the expected part of the job and are reported. This will in turn give a more accurate picture of the media environment, which is imperative for all follow up journalist protection work. A further driver to normalisation is ineffective responses by public authorities, including the police. The absence of meaningful protection to prevent threats, alongside robust investigations and convictions following an incident, itself fueled by and fueling the climate of impunity, further undermines journalists’ safety and security.

The state should prioritise and explore ways in which crimes or threats against journalists and media workers are monitored, with specific criteria for women in journalism due to the scale of gendered threats. All other support offerings emerge from this as it establishes a baseline knowledge of the media environment that will inform all future strategic decisions. The National Action Plan for the Safety of Journalists outlines this through the annual survey delivered by the DCMS, the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) and the Society of Editors, as well as calls for evidence by the Home Office. While these can add detail to the understanding of the broader media environment, the static nature of these forms of data collection prevents a meaningful, accurate and evolving understanding of the issues and the broader environment. Journalists and media workers should be able to report threats (anonymously where necessary) in real time to ensure all incidents are monitored in a manner that can also be analysed over time. PersVeilig, a monitoring platform coordinated by the Dutch journalists union (Nederlandse Vereniging van Journalisten, NVJ), the public prosecution service, the police, and the Dutch Society of Editors-in-Chief enables journalists and media workers to upload details regarding threats to an online platform that then verifies and logs the incidents to help inform journalist protection work developed by state and non-state actors.

The Action Plan, as published, also stops short of advocating for or committing to training or offering tailored support for women journalists who experience online abuse (training in the plan is directed solely at reporting during demonstrations). Well funded and sustainable training both for journalists and police officers (among other state entities) should be available to build understanding of online threats and remedies that can offer practical support and protection. All training for police officers should be compulsory and form a core element of the ongoing training they receive during their employment. Further to this, dedicated support for tackling online threats within the police force, which includes technological expertise around smear campaigns, platform moderation, online communities, and networked abuse coordination between prominent and pseudonymous actors should be deployed within all police services across the UK. This will help rebuild journalists’ trust in the police, while also enabling the police to gain a more detailed, nuanced and accurate picture as to the online harassment landscape that journalists face solely for their work.

The UK Government has signposted the upcoming Online Safety Bill as the legal device needed to protect journalists. However, there are a number of established laws that could be used to address online harassment and threats without depending on this proposed law. What is required is that these laws are used effectively, with designated and specific support for women in journalism due to the heightened risk of online abuse. This is further reinforced by the concerns that the bill could further undermine free expression, the foundation of media freedom through the establishment of a threshold of harm that falls short of the legal threshold. The draft bill establishes a requirement for intervention by both online platforms and the regulator, Ofcom, which would result in the censoring of online content. While there is an exemption for a ‘recognised news publisher’, it is unclear whether citizen journalists, bloggers, freelance or independent journalists would be adequately shielded from the bill’s takedown powers as intended. This is highlighted by Lexie Kirkconnell-Kawana, Head of Regulation at IMPRESS:

While recognised news publishers will be able to appeal platforms’ decisions and raise super-complaints to Ofcom, we are concerned about journalists’ capacity (with limited time and resources already under hostile working conditions) to raise cases with platforms and government regulators to have their free speech rights be affirmed.

Any law that mediates speech (online and off), including policies that could enforce the removal of content, even when framed as safeguarding measures, must be in line with international law and norms in relation to the right to free expression. It must be open to scrutiny and all actions that result in the takedown of content must be accessible to appeal and criticism.

Further to this, the requirement for platforms to be able to adequately govern content in line with the bill’s requirements also challenges the compatibility of a number of tools that journalists depend on to protect themselves and their sources, namely end-to-end encrypted programmes, such as WhatsApp and Signal. According to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) “companies using end-to-end encryption were not exempt from the duty of care, and would have to demonstrate to Ofcom how they are managing risk to their users or face action.” It is unclear how this obligation is compatible with the continued delivery of these services, which could raise significant concerns for journalists and media workers.

As outlined by the International Press Institute (IPI), due to the complex speech environment that is as dependent on government policies as it is on private online platforms, a multi-disciplinary and multi-stakeholder approach must be prioritised. While there are concerns that the Online Safety Bill may breed hostility between the state and online platforms, a meaningful relationship between these actors is vital as it can support and embolden journalists to report threats to both actors, while also making it easier for the state to escalate threats to the platforms for expedited action. A constructive relationship between the state and online platforms could also help establish processes by which systemic changes to the platforms can be brought forward, such as more responsive reporting and appeal processes, transparency built into the content moderation process, as well as the potential of future developments that could further protect journalists and enable them to continue using the online platforms, both within the personal and professional context.

Outside state and platform responsibilities, media outlets and owners, alongside senior editors and managers also have a duty of care to their employees and contractors (including freelancers). This duty should extend to proactive and reactive responses to online harassment and threats, with a similar gender-responsive approach as outlined above to ensure that gendered threats are also protected against.

While the decline in advertising revenue, decreasing readership and inadequate responses to online consumption of news has diminished media outlets’ resources (also extending to in-house legal representation), there are a number of changes that all outlets should incorporate. This includes:

Enhanced psychosocial support for all journalists and media workers (including freelancers);

Enhanced HR programmes and coordination with the newsroom to support journalists and media workers. This can include regular training and capacity building sessions, digital security check-ins, and anonymous incident reporting;

In-House monitoring of media freedom violations in real-time that can shape the outlet’s support offerings and contribute to broader analysis of the media environment;

Coordinated responses to online platforms on behalf of journalists and media workers to proactively respond to online harassment and threats. This includes sharing issues and coordinating with online platforms;

Engaging with relevant state authorities, including the police, to coordinate necessary protective or investigatory support for journalists and media workers, and;

Developing in-house support offerings, which could include alternative housing arrangements for at-risk journalists and digital resources such as password managers and DeleteMe.

Threats of Violence Against Journalists in Northern Ireland

Out of the 84 alerts outlined above from Mapping Media Freedom since the start of 2018, 17 are specific to Northern Ireland (this omits policy changes that may affect Northern Ireland alongside other parts of the UK) and out of the 27 that involve women as the target, seven also are from Northern Ireland.

The reasons for the uptick in threats are complex and numerous but come at a time of heightened tensions due to increased sectarian division, the remnants of a fragmented political environment following the dissolution of the NI Executive, and economic and social uncertainty brought about by Brexit. The movement of a number of sectarian groups into organised crime, such as the trade in drugs and weaponry, and a weak and fragmented response from law enforcement has also contributed to an atmosphere of impunity that has embolden organised crime groups. This was typified by unsolved murder of Martin O’Hagan in 2001 and the recent blanket threats made against Sunday World and Sunday Life, which included threats of imminent physical and car bomb attacks. It is understood that the threats emanated from the South East Antrim Ulster Defence Association (UDA). Similar threats were made against prominent politicians, including local representatives, who made public statements of support for the media outlets. The UDA had made similar threats against other Belfast-based journalists in 2018 and without meaningful actions by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), there are few suggestions that the situation will improve.

The threats by organised crime groups and sectarian organisations was typified by the 2019 murder of Lyra McKee by the ‘New IRA’ as she was covering a riot in Derry. Two years on, as stated above, while charges have been made against an individual, no one has been convicted. This lack of unequivocal action continues to embolden those who target journalists. A journalist who witnessed the shooting has been targeted by online trolls and graffiti labelling her an informant and similar graffiti was sprayed on the memorial of Lyra McKee set up in Derry, with little evidence as to the perpetrators.

Inaction by the police has defined the experiences of too many journalists. Over the last few years, Patricia Devlin, a crime reporter for Sunday World has endured ongoing and escalating abuse and threats for her reporting around organised crime, corruption and the legacy of the troubles. In October 2019, Patricia went public about the abuse, which was “sectarian and misogynistic in nature” she had received as a result of her work. This abuse included a threat to rape her infant son - a threat that has been recently repeated in 2021 via a pseudonymous facebook account - which was signed off with the term ‘Combat 18’, an international neo-Nazi organisation. The abuse has been consistent and utilises a number of different platforms, such as facebook and personal messaging apps. At one point, the perpetrator gained access to Patricia’s phone number and called her. On 12 February 2021, graffiti including a gun crosshair and Patricia’s name was discovered in at least two locations in East Belfast. This threat was reinforced by false allegations made a few months later, on a facebook community page accusing an unnamed journalist of falsifying the threats against them. This included coordinating anonymous calls "claiming to be the UVF" to issue threats and "malicious ‘false flag’ graffiti". While Patricia's name was not mentioned, the described threats align to the threats directed at her. Similar graffiti also targeted Allison Morris, the security correspondent and columnist for The Irish News, which also alleged that she is a MI5 agent. As seen in the threats against the witness to the murder of Lyra McKee, alleging complicity in UK-state entites is a reoccuring threat that, due to the complexities and sensitivities of the political context of Northern Ireland, should not be dismissed as empty threats. By labelling them as agents of a state, unknown perpetrators are signalling to others the complicity of these journalists and therefore a justified target for violent reprisals.

Patrica has reported the threats made against her to the PSNI and the identity of the person behind the threats to her child is known to the service. However, they have been free to leave and return to Northern Ireland with few impediments. When they were known to be in Scotland, inadequate coordination with Police Scotland enabled them to escape arrest, or even being questioned, further opening up Patricia to further threats. Police failings, inaction and inadequate communication with the journalist, which resulted in the ‘constantly changing and contradictory story as to why they [PSNI] have not acted’ led Patricia Devlin in 2019 to lodge a formal complaint to the Police Ombudsman’s office. This decision to act unilaterally, in spite of state inaction (or insufficient action), also led to lawyers instructed by Patricia to issue a legal notice against Facebook to provide the details of an account targeting her. As outlined by the Belfast Telegraph, the legal notice was a “Norwich Pharmacal Order”, which can force third parties to disclose relevant data such as IP addresses and potentially the real names of the users behind the threats. While this would be an important first step in any civil action against the perpetrators, it is a form of private action that was only necessary due to the failures of the state to protect journalists from harm. No journalist should be expected to investigate and confront perpetrators at the same time as being targeted by them. This is a failure of the state that further isolates journalists and could encourage them to step back from the industry if it brings forward threats of violence and insufficient protections.

Potential Remedies

The UK Government National Action Plan for the Safety of Journalists stated this in regards to threats against journalists in Northern Ireland:

The Plan does not, however, draw out those threats into Northern Ireland-specific action, as to do so would be to take them out of their wider context. In addition to the work undertaken by law enforcement agencies in response to specific threats, the Northern Ireland Executive’s Action Plan for Tackling Paramilitarism, Criminality and Organised Crime aims to address the long-term, underlying problem of paramilitary activity.

Due to the severity, regularity and unresolved nature of a number of threats made against journalists and media workers in Northern Ireland, this omission could have severe consequences for continued reporting in the region, as well as the overall safety of journalists and media workers. While this submission understands the complex nature of the political environment, as well as the interplay of devolved and reserved responsibilities between Westminster and Stormont, the failure of the action plan to respond to these threats risks isolating journalists in the region and leaving them with inadequate protections. This is reinforced by documented failings of the PSNI, leaving journalists and media workers in NI, with fewer avenues of recourse or protection. The documented inaction of Northern Irish authorities, namely the PSNI, as well as the severity of the threats facing journalists across the region, demonstrates the importance of the working group being able to respond to violations and protect journalists there. As there are no publicised limitations to the action plan’s utilisation in Scotland and Wales, it can only be assumed that it already can respond to a differentiated legal and political landscape across at least three devolved nations. We would recommend that work is undertaken, as a matter of urgency, to ensure the action plan’s commitments and support offerings are replicated for Northern Ireland. Even if they are delivered differently and in a manner that involves different, more tailored, engagement with the Northern Irish political environment, this work should start as a matter of urgency. This should include collaboration with Northern Irish stakeholders, such as the newly formed all-party group on press freedom and media sustainability at the Northern Irish Assembly. Working with this and other relevant stakeholders will ensure the action plan and the national committee would have a strong bedrock of support to complement and reinforce as threats to journalists increase.

Further to this, there are a number of ways the action plan can support journalists and media workers in Northern Ireland. By ensuring all investigations into threats and attacks aimed at journalists are monitored and engaged with by the relevant authorities in the broader UK, as part of the standard diplomacy and inter-departmental dialogue, will ensure they are carried out with the necessary urgency and transparency. This will also foster avenues of greater collaboration and support across jurisdictions where necessary to ensure all crimes are investigated to the fullest. As demonstrated in the threats aimed at Patricia Devlin, where the perpetrator left Northern Ireland for other parts of the UK, as well as the non-national nature of online platforms, threats in Northern Ireland are seldom restricted to that region alone.

Due to the geographic proximity, similar media and legal landscapes and closeness of political institutions, Great Britain also offers an invaluable location for respite support and residency programmes for at-risk journalists. This can offer journalists an opportunity to continue their work in a safe location, enable them to source the necessary psychosocial support and avoid flashpoints if they are already under threat. All residency programmes should also take into consideration support for family, including young children as part of a gender-responsive approach as outlined above.

Recommendations For The UK National Action Plan for The Safety of Journalists

The National Action Plan for the Safety of Journalists is a step forward for the UK, ensuring a coordinated and structured approach to journalist protection that can take both a proactive and reactive stance towards all threats.

However, based on the published plan, there are a number of gaps that need to be addressed as the action plan is evaluated:

There are few aspects of the action plan that address the specific threats facing women in journalism. To ensure the gender-responsive approach, as outlined earlier in this submission, is substantial enough to build trust in the plan this should be prioritised by all state and non-state members of the national committee.

The plan outlines a number of planned training programmes for state authorities, most notably the police, for protecting or supporting journalists during the course of their reporting. This is a welcome addition to the action plan but it is silent as to whether these will be optional or additional to the standard and required training that police officers are expected to complete. To ensure journalist protection is consistently applied across all police departments and individual police officers, all training for police officers as highlighted in the action plan should be compulsory and form part of the required ongoing training police officers are expected to complete. These programmes should be also mandated for all existing officers and those entering the service.

In section 1 ‘Increase our understanding of the problem’ the action plan outlines a number of data and evidence sources it will support to build its understanding of the threat environment within which journalists and media workers are expected to work. While the Home Office consultation and the DCMS, Society of Editors and NUJ survey will add significant detail and nuance to the action plan’s deployment, these cannot monitor the evolving state of media freedom as they are not ongoing monitoring mechanisms. These outlets should be augmented by an ongoing monitoring mechanism that can be contributed to by journalists and media workers, alongside journalist protection organisations and trade unions. This can be developed as a UK-standalone platform or can be delivered by the utilisation of existing monitoring platforms, such as Mapping Media Freedom or the Council of Europe Platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists. Standalone mechanisms that the action plan could look to include PersVeilig, which monitors, documents and analyses threats to journalists and media workers in The Netherlands and SafeJournalists which covers the Western Balkans, including Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo, Albania, Croatia, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Any monitoring mechanism should include criteria to identify gendered threats to ensure that specific threats against women are incorporated into the monitoring methodology.

In the action plan’s introduction, it states that ‘[p]erhaps of most importance, the Plan is a living document.’ This is an important clarification and demonstrates the willingness of the national committee to ensure that the plan will evolve as the threat environment does. However, to embed transparency and openness, the committee should make public the planned ongoing evaluation, monitoring and amendment plan, while also committing to regular open and participatory evaluation to ensure the action plan does respond to changes adequately.

As part of this evaluation, the research base that the action plan uses should also evolve to incorporate new thinking and showcase the academic and practitioner expertise that has been brought to bear on the field of media freedom and journalist protection. While also strengthening the basis upon which the action plan is built and evaluated, it will also ensure the plan is a useful space of bringing together expertise that can be used to build trust in the action plan and support future work in this field.

The action plan currently focuses on non-state actors as the perpetrators of threats against journalists and media workers. While they play a significant role in the threat environment, to ignore state actors is only to work on a partial view of the threats facing journalists. To ensure all threats are addressed without prejudice, bias or favour, the action plan and national committee must be able to respond to threats from state actors, such as police officers and politicians. Only with this full view, will journalists trust the action plan as a genuine support offering that addresses all perpetrators equally.

Further to the last point, the action plan should also include powers to ensure the national committee can monitor investigations of crimes against journalists and media workers. This is vital to tackling the climate of impunity while also establishing a basis upon which recommendations can be drawn to improve future investigations. This is similar to the comments made by Damien Collins MP who called for a systematic review into the handling of crimes against journalists by police officers to ensure all failings are addressed and learnt from.

If you would like to request more insight into our findings, or would like to suggest an addition to our work reach out to us at data@womeninjournalism.org. For media inquiries reach out to us at press@womeninjournalism.org.