2021 Annual Press Freedom Report

The most dangerous but resilient year for women journalists

Murdered Women Journalists in 2021

About CFWIJ

What we do?

The Coalition For Women In Journalism is a global support organization for women journalists. We pioneered a mentorship program for mid-career women journalists across several countries worldwide and are the first organization to focus on the status of free press for women journalists. The CFWIJ brings together journalists and related bodies to cultivate a safe and conducive environment for women journalists globally and help them navigate the industry. Our goal is to build a strong network enabling women journalists to work safely and thrive.

Campaigns

In 2021 the CFWIJ launched several worldwide campaigns to celebrate women journalists, demand justice for women braving severe violations for the right to report freely and independently, defend free speech and ensure the right to information. With our global campaigns and events throughout the year, we aimed to highlight challenges and issues that female reporters face every day and report on violations against them in over 92 countries.

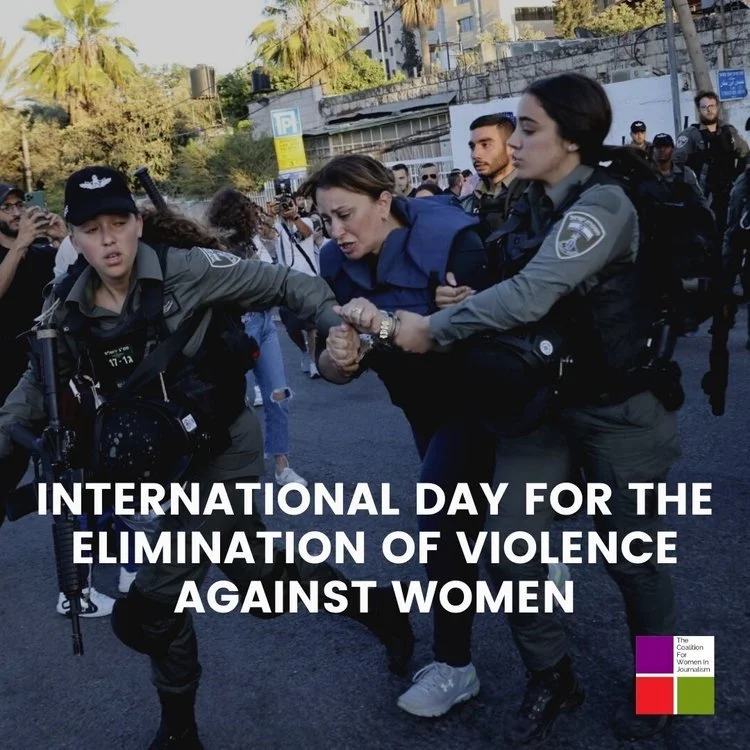

On Human Rights Day, we drew attention to violence against women journalists with a special focus on countries where violations against press freedom escalated in recent months. We launched a powerful campaign on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women this year and called on the international community to recognize that for women journalists, job hazards and gender-based violence often amount to the same thing. Our message resonated with women journalists across the globe.

On November 2, the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists, the CFWIJ extended support to women and LGBTQI+ journalists worldwide, who face mistreatment and abuse because of their gender and their reportage. Journalists from around the world joined our campaign to stress that impunity begets violence and demanded justice for crimes against women and LGBTQI+ journalists everywhere.

We paid tribute to all hardworking and dedicated women journalists on International Women’s Day for their extraordinary contributions to press freedom despite having the odds stacked against them. While this year’s edition focused on challenging the current order, the CFWIJ persists in confronting the media industry's ever-present gender bias and inequality. We brought some powerful messages from our network on Women's Day. Women journalists shed light on how they overcome the many obstacles they face in their line of work and shared what drives them to continue striving for press freedom.

On World Press Freedom Day, which stresses journalists' fundamental rights and freedoms, the CFWIJ amplified the violations faced by women journalists. We compiled the threats, attacks and harassment braved by women journalists and provided a comparative analysis of violations witnessed in 2021 and 2020.

Country specific research

The CFWIJ has also focused on specific countries and individual women journalists. We highlighted major events, such as COVID-19, Afghanistan Evacuations, US protests, and others which were crucial for their impact on press freedom. Moreover, we have compiled resourceful lists of women journalists reporting in the MENA region, covering COVID-19 on the frontlines, BLM protests, farmer protests in India, and black women journalists to follow.

Threats and violations against women journalists

In 2021, the CFWIJ revived its Twitter campaign to raise awareness on #ThreatsToWIJ - abbreviated from Threats to Women in Journalism. This campaign, first launched in 2017, focused on amplifying threats faced by women journalists in the industry and in the field. Online harassment, physical assault and threats to families of journalists were common violations faced by women journalists around the world.

Our campaign in 2020 featured a special focus on Pakistan, prompted by the brutal murder of Baloch journalist Shaheena Shaheen and the incessant online trolling of women journalists in the country. The CFWIJ drew attention to vicious social media attacks, doxing and hacking attempts faced by women journalists in Pakistan, often by accounts affiliated to the ruling party and conservative, right-wing constituents. #ThreatsToWIJ made the top 50 trending topics in Pakistan on September 15, 2020.

On September 22, 2020, we launched a global campaign to discuss various forms of threats and attacks against women journalists. The campaign, designed as an interactive chat on Twitter, used the #ThreatsToWIJ hashtag to bring together women journalists, activists and rights advocates. This platform facilitated journalists to share their testimonies and propose remedies to enable women journalists to perform their jobs in a free and safe environment.

Monthly reports

In 2020 the CFWIJ also started publishing monthly reports, generating a monthly database of violations against women and LGBTQ+ journalists world over. These reports highlight the different types of cases we identified each month - ranging from arrests and detentions to physical assaults and online harassment. The reports provide periodical markers to what press freedom looks like for female and LGBTQ+ reporters worldwide.

Advocacy

In 2021, we continued this practice, along with building on the advocacy branch of our organization. Launched in 2013, the advocacy branch helps the CFWIJ make the issues and challenges women journalists face every day more visible. Our vigilant monitoring, and diligently collected data, indicate an alarming rise in threats to women and LGBTQ+ journalists worldwide.

2. Objective Of The Report

This report presents a review of the threats women journalists have faced in 2021. Throughout the year, the CFWIJ monitored many cases of violence and threats against women journalists. The year 2021 saw an escalation of violations against women journalists who were subjected to violence both online and offline. We reported on devastating killings, kidnappings, imprisonments, legal and physical harassment, attacks in the field, state suppression, sexist attacks, and numerous other violations that endanger press freedom. The CFWIJ documented attempts by oppressive regimes aiming to silence critical journalists through threats, intimidation and the weaponization of law and state institutions. The report reflects the deteriorating conditions in which women journalists continue to work and how they remain vulnerable to attacks on them.

The CFWIJ has prepared this report using first-hand information, public-access news, and updates from different regions across the world. Cases that have not been publicly reported have been excluded from this document to maintain the individual’s privacy.

This report was supported by Craig Newmark Philanthropies.

Executive Editor: Kiran Nazish

Editor: Jaza Aqil

Data, research and writing: Aimun Faisal, Ayesha Khalid, Ceren İskit, Damla Tarhan Durmuş, Dia Morina, Jaza Aqil

Design: Damla Tarhan Durmuş

Overview: Major violations against women journalists in 2021

In 2021, violations and threats against women journalists were increased by 13.6% compared to 2020.

Ma Hmu Yadanar Khet Moh Moh Tun, a video journalist with the Myanmar Pressphoto Agency, and her colleague, photographer Kaung Sett Lin, were critically injured and subsequently arrested by the military forces while covering a peaceful anti-regime protest in Yangon on December 10, 2021.

The year 2021 presented a bleak picture for press freedom worldwide. The CFWIJ recorded a total of 831 cases of violations against women journalists throughout the year. A sharp increase since 2020 when we witnessed 731 such cases. We saw the number of incarcerated women media workers reach a record high - as many as 63 remained behind bars on December 31, according to the CFWIJ’s findings, with at least 20 women journalists jailed in 2021 alone. At least 12 women journalists were killed while numerous others were subjected to various forms of state suppression, legal harassment by state and non-state actors, physical assualts and harassment, sexual assaults and harassment, and online violence.

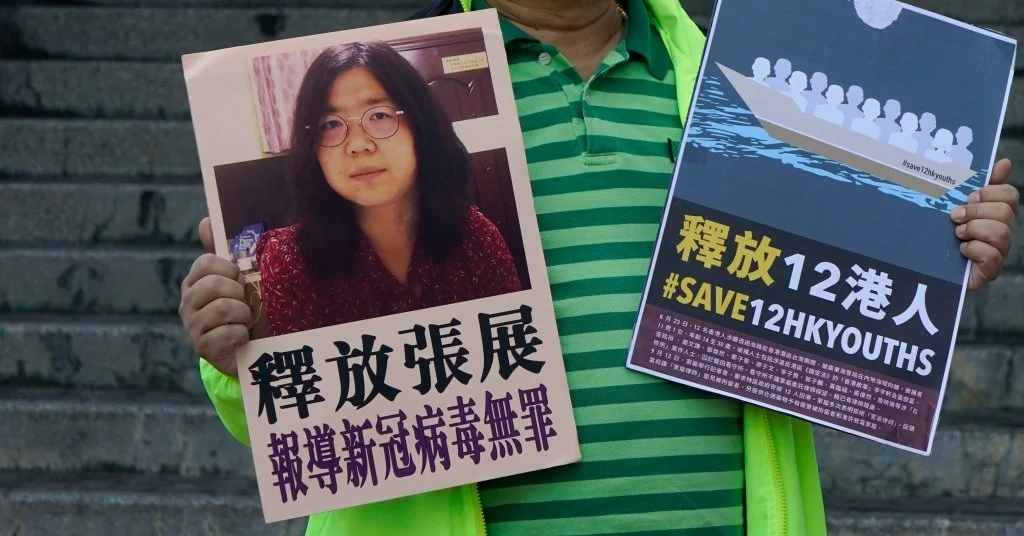

The economic toll of Covid-19 that hit in 2020 carried forward to 2021 along with the health and social implications of the pandemic. Even as countries and newsrooms adapted to intermittent tightening and easing of restrictions, women journalists worldwide continued to bear the brunt of increased care work alongside the demanding nature of the job. And yet, they reported on the pandemic from the frontlines, responding to the situation each time the pandemic reared its head in the form of a new variant, and kept citizens well informed. For many, this came at the cost of their own safety. Threats by the virus aside, critical journalists were also forced to deal with government retaliation for exposing mishandling of the pandemic, monetary irregularities and graft, and for merely holding elected representatives accountable for their actions to secure public health. Prominent among these were the cases of Zhang Zhan in China and Rozina Islam in Bangladesh, with the former yet languishing in prison even as her health deterioates dangerously, and the latter continuing to face legal harassment at the hands of the state. In both cases, the only crime the journalists committed was questioning their respective government’s mishandling of the pandemic.

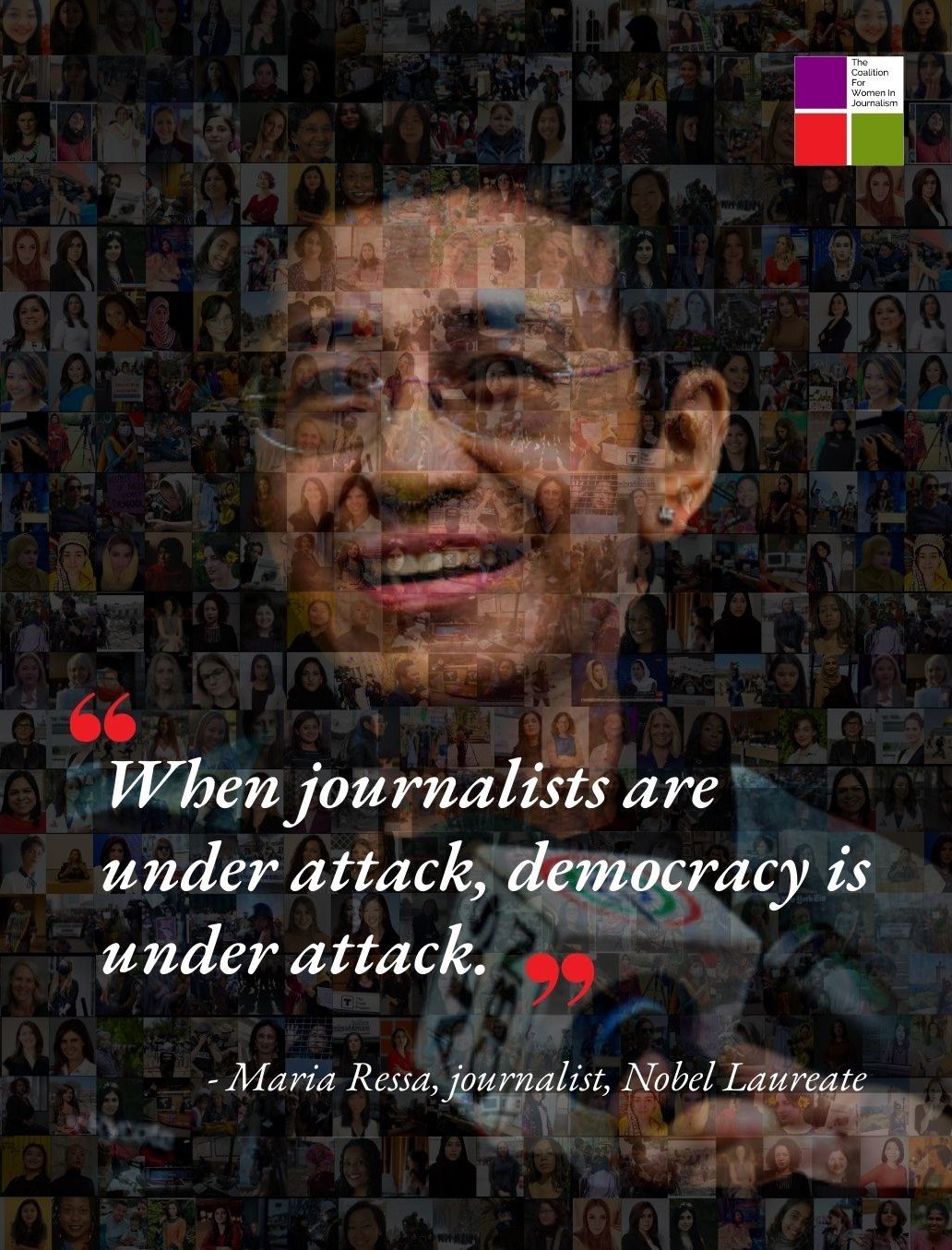

When speaking of legal harassment of journalists at the hands of the state, one cannot ignore the trials and tribulations of Maria Ressa in the Philippines. In October, the CFWIJ welcomed the decision of the Norwegian Nobel Committee to honor Maria with the prestigious Nobel Prize for her “efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace”. Maria has been a vociferous critic of the President Rodrigo Duterte’s government and the deadly “war on drugs” he launched in 2016. For repeatedly holding power to account, the Nobel Laureate and her team have been targeted with a series of state-linked legal cases, investigations and online attacks. Even as the committee recognized Maria as a representative of all journalists who stand for freedom of expression and press freedom, a senior member of the Philippine cabinet filed a new libel against Rappler, a digital media company for investigative journalism, which she co-founded in 2012 and still heads. This lawsuit is the eighth active legal case against Maria brought by the state. Her legal battles in seven cases, including an appeal against her 2020 conviction for criminal cyber libel, in which she faces up to six years in prison, are still ongoing.

Far from acting as a deterrent, however, the Philippine government’s long drawn out legal battles with Maria, have only made her bolder and stronger. In December, as she collected her award, after thwarting the state’s attempts to prevent her from traveling to Oslo, Maria stood tall and defiant as a defender of the free press. Her story, though prominent, is not an isolated one. In 2021 alone, the CFWIJ documented over 175 cases of women journalists being subjected to legal harassment for their reportage.

Throughout the year, we saw legal harassment employed as a common tactic to gag critical journalists. Under the garb of anti-terrorism laws, increased censorship ostensibly to counter “fake news” and the pandemic, oppressive regimes sought to embroil critical journalists and dissenting voices in legal battles. In several cases, as in the case of Turkey, this led to women journalists landing in pretrial detention or facing prolonged prison sentences. In Iran, we saw the arrests of Rahil Mousavi, Mehrnoush Tafian and Narges Mohammadi, whereas in India we saw legal charges brought forth against Rana Ayub and Barkha Dutt, among others. In Russia, the draconian “foreign agents” law was liberally employed to engage women journalists in legal battles.

Moreover, states around the world continued to introduce new laws to encroach on the freedom of the press. China introduced fresh curbs banning private investment in media houses and broadcasting, El Salvador president proposed a new law - similar to one we have seen abused in Russia - requiring media outlets and journalists with foreign sources of funding or income to register as “foreign agents”, the Nigerian government banned Twitter and Pakistan introduced repressive Pakistan Media Development Authority while Ethiopia ramped up arrests to squash coverage on the on-going civil war in the country.

Apart from state suppression in the form of legal harassment and imprisonment, women journalists also faced threats from other state-linked institutions. We recorded instances of police and military violence against female media workers as well as slander campaigns run by pro-government media outlets against critical journalists and abductions. In Myanmar, for instance, the military junta resorted to brute force against journalists critiquing the February coup and reporting on protests against the military regime. The deeply concerning violations faced by Ma Thuzar, Thin Thin Aung, Myo Myat Myat Pan, Kay Zon Nwe and Ma Hmu Yadanar Khet Moh Moh Tun stand as testament to the dangers facing women journalists in the country.

Threats to women journalists increased world over not just in the physical space but also in the online realm. The rise of right-wing populists and increasing polarization of societies across the globe coupled with rapid spread of misinformation amid lack of regulation by social media giants left women journalists vulnerable to threats both online and offline. At least 96 women journalists were targeted with organized trolling and slander campaigns online in 2021. In several instances, the personal details of women journalists were also made public online thus exposing them to further attacks in the physical space as well.

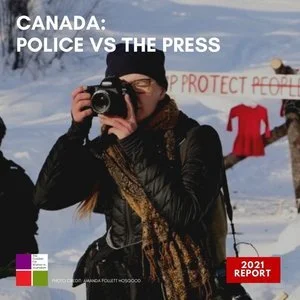

Appalling examples of risks to women journalists were witnessed in Canada, Argentina and Northern Ireland. According to our findings, Canada proved to be the most hostile virtual space for women journalists in September when over 20 women journalists of color received vile and threatening emails after right-wing politician Maxime Bernier tweeted a provocative message to his followers. Displeased by their coverage of his work, and their line of inquiry, Bernier encouraged his supporters to “play dirty”, sparking a violent and targeted harassment campaign. He even went so far as to publish the email addresses of some of the journalists online, exposing them to online abuse. Although Bernier’s tweets were later taken down by Twitter because they violated community standards, they paved the way for hostile attacks against journalists.

Subsequently, a stark reminder of digital vulnerabilities for those holding power accountable unfolded in Canada. Women journalists were sent racially charged and deeply gendered abuse and threats online by a single malicious email address. Despite widespread condemnation of the attacks, the local authorities did little to prevent or investigate the attacks. The following month, at least five more women journalists of color in the country were targeted online.

Meanwhile, Argentina and Northern Ireland saw the safety of journalists Sandra Borghi and Patricia Devlin, respectively, severely compromised because of attacks on them online. The former was subjected to virtual identity theft, which endangered not just her but also her network of friends and colleagues, while the latter continued to face vile and deeply gendered threats against herself and her minor son.

The deeply gendered nature of threats to women journalists online was both reflective and reflected in violations against women journalists offline. Our reports in 2021 also shed light on the prevalent threat of sexual harassment faced by women journalists. This particular violation, which directly impacts women’s role in the news media industry, is typically brushed under the rug. In the past year, however, several women journalists from different countries around the world came forward with their experiences of surviving sexual misconduct. Throughout the year, the CFWIJ recorded at least 27 cases of women journalists being subjected to some form of sexual harassment while on the job. Shelley Ross in the United States, Greta Beccaglia in Italy, and Mariana Romero and Carolina Ponce de Leon in Argentina, stand as recent examples. Moreover, the CFWIJ also documented instances of accused harassers being appointed to positions of power for example M Radhakrishnan in India.

The year 2021 saw multiple threats to women journalists apart from the most notable threats highlighted above. At least 72 of them were obstructed in the field, 65 faced expulsion from work, 52 were subjected to some form of threat or miscellaneous intimidation tactics, 26 women journalists faced some form of workplace harassment, 17 were subjected to verbal harassment and three had their accreditation revoked. High on our radar in 2021 were Turkey, Afghanistan, Belarus and Russia. Read on below for our in-depth review on threats to women journalists in regions around the world as well as details of some of the most horrific attacks on women journalists this year such as the targeted killing of Yemeni journalist, Rasha Abdullah.

Photo Credit: Darrin Zammit Lupi/Reuters

5. Murder Count

This year, we recorded 12 killings of women journalists worldwide. Female reporters were killed in Afghanistan, Kenya, Yemen, Algeria, Palestine, the United States and Cameroon. The number of murders witnessed in 2021 increased by 100% as compared to 2020.

Mursal Wahidi, Sadia Sadat, and Shahnaz Roafi, Afghanistan

Mina Khairi, Afghanistan

Rebecca Jema Iyabo, Cameroon

Tin Hinan Laceb, Algeria

Lynn Murray, Aviva Okeson-Haberman, United States

Kate Mitchell, Kenya

Reema Saad, Palestine

Rasha Abdullah al-Harazi, Yemen

Najma Sadeqi, Afghanistan

Afghanistan

On March 2, Mursal Wahidi, Sadia Sadat and Shahnaz Roafi were shot dead by terror outfits in Afghanistan. All three victims worked at Enikass Radio and TV. This was the first attack, in what has emerged as a pattern of violence on Afghan women journalists by fundamentalist groups. The brutal triple murder in a single day understandably sent shockwaves around the world.

On June 3, Mina Kheiri, a journalist and media worker for Ariana Radio and Television was killed in an IED blast in Pul-e-Sokhta area of Kabul. Her mother reportedly died in the same attack while her sister was critically injured. According to Ariana News, the family was out shopping when they were attacked.

After a bomb attack at the Kabul airport on August 26 left more than 170 people dead, the situation for Afghan women journalists is deteriorating. Three journalists, including one woman journalist, were among the casualties. Najma Sadeqi, a young Afghan YouTuber from the Afghan Insider channel was at the airport trying to secure an evacuation flight when the bomb was detonated.

Cameroon

The very first week of 2021 was marred by a separatist attack on a convoy in Njikwa, Cameroon, which left journalist Rebecca Jema Iyabo. The journalist was killed on January 8, 2021, along with four military officials, when a bomb exploded near the convoy. A video posted on the internet showed the convoy vehicles completely wrecked and engulfed in flames.

Rebecca, popularly known as Becky Jeme, was the top Divisional Delegate for Communication for Momo. Her death came as a shock to her friends and fellow journalists, who described her as a person full of life.

Algeria

On January 27, Algerian journalist Tin Hinan Laceb, of ENTV’s Amazigh channel (TV4), was reportedly killed by her husband. Tin Hinan Laceb left behind two daughters and a remarkable legacy built over the years she worked as a presenter for TV4 and as a website specialist for Arab and Amazigh news.

United States

On March 22, 2021, former photo director for Hearst and Conde Nast Lynn Murray was shot dead in the United States. The journalist was one of 10 victims of the shooting in King’s grocery store in Boulder, Colorado. Lynn, a loving wife and devoted mother of two, was a founding member of Marie Claire’s U.S.premier issue in 1994 and contributed immensely towards its success. She had also worked for The Cosmopolitan and Glamour magazines.

The following month, on April 23, journalist Aviva Okeson-Haberman was found dead in her apartment in Kansas City, Missouri, US. She was killed by a bullet that pierced through her window. Only 24 years old, Aviva was an intern at KCUR before joining the station in June 2019 as the Missouri politics and government reporter.

Palestine

May saw the death of Palestinian journalist Reema Saad, who was killed in a bombing on the 13th of the month. Reema was killed in her apartment alongside her children and husband when Israeli forces attacked civilian residences in the city of Gaza. The attack came as targeting of Palestinian civilians by Israeli forces surmounted after the expulsion orders for Palestinian families residing in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood. The incident highlighted the extremely dangerous conditions in which Palestinian journalists operate.

Yemen

November saw the devastating killings of two women journalists. Yemeni journalist Rasha Abdullah al-Harazi and her unborn child were killed in a horrific car bombing in Aden on November 10, 2021. Her husband, journalist Mahmoud al-Atmi, who was driving her to the hospital when they were targeted, was also critically injured.

Kenya

On November 23, the police launched a probe into the killing of Kate Mitchell, a worker for BBC Media Action. Kate was found dead in her hotel room in Nairobi. Police told local media that Kate was likely killed by strangulation and a homicide investigation has been opened.

Photo Credit: Natalia Fedosenko/TASS via Getty Images

6. Imprisonments

At least 21 women journalists were jailed in 2021, bringing the total number of incarcerated women journalists across the globe to 63. According to our data, the world saw a 31.24% increase in the number of women journalists put behind bars in 2021 compared to the previous year. Although 19 women journalists were also released the number of women journalists still languishing behind bars is extremely concerning.

China replaced Iran as the world’s biggest jailer of women journalists in 2021, with at least 17 incarcerated. At least seven of the imprisoned journalists are Uyghur women with little to no information available regarding their arrests or incarceration status. Given the magnitude of China’s human rights violations against its Muslim Uyghur population and extensive press censorship, the actual number of Uyghur journalists jailed is expected to be higher than reported figures. In the second place, Iran still had 10 women journalists in prison in 2021 as state authorities remain relentless in their attacks on press freedoms. Belarus stood in third place with 10 women journalists incarcerated, eight of whom were jailed in 2021. Myanmar, another country that has relentlessly persecuted media workers, had at least eight women journalists behind bars in 2021. The highest rate of imprisonments was witnessed in Belarus, which moved up from sixth place on the CFWIJ’s list of jailers of women journalists in 2020.

Meanwhile, at least three women journalists remain incarcerated in Turkey, as many in Vietnam, two in Ethiopia and Egypt each, and one each in Cambodia, Burundi, Laos, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Russia. Read on for more details about women journalists imprisoned in each country.

China

Photo Credit: AP Photo/Kin Cheung

Cheng Lei. Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Sophia Huang Xueqin, freelance journalist and #MeToo activist, went missing on September 19, 2021, the day before she was to leave the country to pursue a master’s degree at the University of Sussex in the United Kingdom. Her arrest was later confirmed under charges of “inciting subversion of state power”. The journalist was also detained previously between October 2019 and January 2020 under charges of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” for reporting on mass protests in Hong Kong.

Gulmira Imin was arrested on charges of “splittism, leaking state secrets, and organizing an illegal demonstration” in July 2009. She participated in a major demonstration protesting the deaths of Uighur migrant workers in Guangdong Province on July 5. Gulmira was taken into custody after authorities alleged she had organized the protests. She was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Atikem Rozi has been in prison since February 2014. She was detained at an undisclosed location in Xinjiang on charges of participating in alleged separatist activities led by Ilham Tohti, founder of the Xinjiang news website Uighurbiz.

Wang Shurong has been behind bars for more than five years now. She had been volunteering for several years as a citizen journalist with the human rights website 64 Tianwang when she was detained in February 2016.

Chimengul Awut was arrested in July 2018. She was sent to a re-education camp for her contribution to a novel that the Chinese government denounced.

Zhang Zhan has been behind bars since May 2020 and is currently imprisoned in Shanghai. Zhang was arrested after she criticized the authorities’ measures to contain COVID-19 on her Twitter account. The journalist was formally charged with undermining the authorities. Her health has significantly deteriorated in prison and she is currently on the brink of death.

Cheng Lei was officially arrested after almost six months of detention on charges of "illegally supplying state secrets overseas". She was working as a news anchor for the state-owned news channel China Global Television Network and had been there for eight years.

Haze Fan was detained in December 2020 on suspicion of endangering national security. She was escorted from her apartment and currently remains in the custody of Chinese authorities. She is a Chinese citizen employed by an American publication house.

Wang Linlin, director and contributor at provincial news platform Hui Town Site, was sentenced to nine years in prison on charges of extortion and picking quarrels and provoking trouble for her coverage of sensitive social issues. She has been behind bars since April 12, 2018.

Several Uyghur journalists remain imprisoned in China. The CFWIJ was available to identify the names of seven such women, but given the extensive suppression of news regarding the state’s atrocities against its Uyghur population, details about their arrests or status of detention could not be verified. The number of imprisoned Uyghur journalists is expected to be higher than the publicly available figures.

Guzelnur Qasim, Kashgar Uyghur Press

Mahinur Hamut, Kashgar Uyghur Press

Anargul Hekim, Kashgar Uyghur Press

Ayshem Peyzulla, Editor, Xinjiang Education Press

Mahibeder Mekhmut, Editor, Xinjiang Education Press

Aynur Tash, Ürümchi People's Radio Station

Baqtygul Oralbai, Kuitun Daily News reporter

Iran

Azar Mahdavan

“We can say that freedom of expression is the same in all third world countries, and this is not a matter for men and women. The lack of specificity of expression is reflected in the media.”

- Azar Mahdavan

Speaking to CFWIJ, Azar Mahdavan, correspondent of MEHR News Agency said, “There are some issues that restrict the profession of female journalists. For example, a woman in Iran cannot work as a journalist in a war environment and it is considered appropriate to have more male reporters in these environments. I am not allowed to work in such an environment even though I work in the international service.”

Askari Zadeh was first arrested by the police in February 2008, while collecting signatures for the "One Million Signatures" campaign at Tehran's Daneshjou Park. She was charged with “acting against national security” and was held in Evin Prison.

Zeynab Jalalian was arrested in 2008 and sentenced to death under the charge of Moharebeh [waging war against God]. She was arrested for her alleged membership to the Party for Free Life in Kurdistan (PJAK), an armed Kurdish opposition group.

Mojgan Sayami was arrested for the first time in October 2017. Security forces raided her house and detained her for 27 days after which she was released from prison on bail. The journalist was then arrested in Tehran for the second time in April 2019 and shifted to Ardabil Prison after she was accused of blasphemy, insulting the Supreme Leader of Iran and disturbing public opinion. In 2021 she continued to languish in prison awaiting trial.

Sepideh Qoliyan has been imprisoned since June 21, 2020. She was imprisoned after being handed a five-year sentence for covering a rally by the Haft Tappeh sugar mill workers, who were protesting unpaid wages. Prior to that the journalist was arrested in November 2018 in Shush for reporting on the rally and released on bail on February 9, 2020. After the verdict was announced, she was put behind bars again in June 2020 and remained in jail in 2021.

Zoreh Sarve was arrested in March 2020. She was charged with insulting the founder of the regime, propaganda against the regime and conspiracy against national security. Zoreh was sentenced to three years and ordered to read the Quran as punishment.

Nada Sabouri was arrested by representatives of the Tehran prosecutor’s office in August 2020 and taken to Evin Prison in Tehran to serve a sentence of three and a half years. She was charged with “assembly and collusion” for protesting prison conditions in Evin Prison in 2014.

Shabnam Ashaouri, the editor of Aghahinameh, an economic bi-monthly specializing in the working class, was arrested from her home on October 4, 2020, by the Revolutionary Guard intelligence officers in plain clothes and remains in prison

Alieh Motalebzadeh was summoned to report to Tehran’s Evin Prison in October 2020 after the appeals court upheld the three-year sentence awarded to her in 2016 on charges of propaganda against the state and assembly and collusion. She was earlier arrested in November 24, 2016, and temporarily released 25 days later on bail on December 19 with a surety of 300 million Toman imposed on her. She remained in prison in 2021.

Nooshin Jafari was arrested in February 2021 and transferred to Qarchak Prison to serve a four-year prison sentence. She was imprisoned on charges of spreading anti-establishment propaganda and insulting sanctities and remains behind bars.

Rahil Mousavi, a freelance photojournalist, was arrested on November 9, 2021 over unspecified charges and remains in state custody. The journalist was taken to an undisclosed location.

Belarus

Photo: АВ / Белсат. Katsyaryna Andreyeva, Darya Chultsova

The Coalition For Women In Journalism reached out to the Belarusian Journalists Association (BAJ) to learn the latest updates.

“This year we have faced an unprecedented level of repression against journalists. (…) Last year’s widespread detentions and administrative arrests of journalists were mainly replaced by arrests on criminal charges, where journalists face up to 7 years in prison. This is a major crackdown on independent media and brutal suppression of free speech.”

- Barys Haretski, Deputy Chairperson, BAJ

Milana Kharytonava. Photo Credit: Facebook

Katsyaryna Andreyeva has been imprisoned since November 2020, along with her colleague Darya Chultsova for live streaming a protest in Minsk. Both the journalists were convicted for violating public order and sentenced to two years in prison each.

Alla Sharko, a human rights activist and program director at the Belarus Press Club was arrested on December 22, 2020, along with her colleagues. Authorities raided the apartments of detainees and their offices at the Press Club. Alla was charged with evading payments of taxes and fees on an especially large scale. She remains in prison still.

Ksenia Lutskina has been in prison since December 2020. Ksenia was first implicated in the investigation against the Belarusian Press Club in August 2021 new criminal charges were brought against her. There is little information about the case since the defense lawyer signed a non-disclosure agreement. The most alarming fact is that Ksenia has developed regrowth of a tumor she was previously treated for and is severely ill but continues to remain behind bars.

Valeria Kostyugova, an independent analyst and editor of the Belarusian Yearbook, was detained on June 30, 2021, when the State Security Committee of the Republic of Belarus raided her house. She was held at a detention center on Akrestsin Street. According to news reports, Valeria was charged with seizing power and conspiracy to seize power under the criminal codes of Articles 361 and 357.

Alena Talkachova, Tut.By reporter, was detained during police raids on the offices of TUT.BY media and apartments of media workers in May 2021. The journalist was charged with tax evasion and faces up to 12 years in prison.

Volha Loika, political and economic editor at Tut.By, was another journalist detained during the mass police raids on employees of the news outlet. Volha was detained on May 18, 2021 and charged with evasion of taxes and fees of especially large amounts, under Article 243 of the country’s criminal code.

Marina Zolotova, editor-in-chief of Tut.By, was arrested during police raids on the news outlet and its employees in May 2021. She faces up to seven years in prison. The journalist was also heavily fined in 2019 on charges of unauthorized access to information of government-owned news agency BelTA.

Iryna Leushyna, chief editor of BelaPAN news agency, was detained on August 18, 2021, along with accountant Katsyarana Boyeva and former director Dzmitry Navazlylau. Police searched the homes of staff members and also raided the agency’s offices in Minsk. The detainees were subsequently sent to prison.

Irina Slavnikova, a Belsat TV representative, was illegally detained at Minsk Airport as she arrived with her husband from Egypt on October 29, 2021. She was reportedly sent to prison for 15 days by court under charges of sharing “extremist” content on her social media. She has remained in prison since.

Myanmar

Photo Credit: AP

Photo Credit: AP

Photo credit: EPA-EFE/LYNN BO BO

Photo Credit: Khin Maung Win/AFP

Photo Credit: Reuters

Photo Credit: Thein Zaw/AP

Shwe Yee Win, a freelance journalist, was arrested along with other media workers in a series of arrests by the military junta shortly after its takeover of the country in February 2021. Cracking down on resistance to the coup, the military and police forces made sweeping arrests across Myanmar picking up hundreds of journalists, activists, protestors and members of the opposition after the coup. Some of the detainees were later released but Shwe remains incarcerated since February 11. No further details about her detention were given.

Htet Htet Khine, a freelance producer for BBC Media Action, was arrested by military authorities on August 15, 2021 along with her colleague Sithu Aung Myint, contributor to US Congress-funded broadcaster Voice of America and columnist for independent local magazine Frontier Myanmar. Htet Htet was charged under Section 17(1) of the colonial era "Unlawful Association Act'' for allegedly working for a banned radio channel and harboring Sithu Aung Myint, who was evading an arrest warrant. If Htet Htet is convicted, she could face up to three years in prison.

Ma Thuzar, freelance journalist, has been under arrest since September 2021 after junta forces abducted her. The journalist was held incommunicado for at least five days before the authorities confirmed her arrest on September 5. The journalist, who had extensively covered anti-junta protests and contributed to Myanmar Pressphoto Agency and the local Friday Times News Journal, was in hiding for months before her arrest. In May, the authorities raided her home and reportedly detained her husband for five days in hopes of finding the journalist. Ma Thuzar was initially kept at military detention centres in Yangon and reportedly charged under Article 505(a) of the penal code for incitement and spreading false news, but her current whereabouts remain unclear. The loosely defined provision under Article 505(a) criminalizes “any attempt to cause fear, spread false news or agitate directly or indirectly a criminal offense against a government employee” or that “causes their hatred, disobedience, or disloyalty toward the military and the government” and carries a maximum sentence of up to three years in prison.

Mya Wun Yan (Hla Yin Win), editor-in-chief of the Than Lwin Thway Chinn Journal, was arrested on July 20, 2021 after authorities raided her residence in Taunggyi, Shan state. The journalist and her two daughters, who are also reporters, were taken to an interrogation center in blindfolds. The former was charged under Article 505(a) of the penal code and reportedly shifted to Taunggyi’s Taung Lay Lone Prison while the latter were released with a warning after a week of interrogation. Around 30 security personnel reportedly participated in the raid at the journalists’ home and confiscated phones, laptops and cameras. Mya Wun Yan remains incarcerated since.

Nang Nang Tai and Nann Win Yi, editor and reporter of Kanbawza Tai news, respectively, were arrested on March 24, 2021, from Hopong, Shan state, after covering protests against the military junta, and have been jailed since. On December 10, 2021, they were each sentenced to three years in prison under Article 505(a) for incitement by a special court at Nyaung Shwe Taung Lay Lone Prison. The news outlet’s publisher Tin Aung Kyaw was also arrested in March and handed the same sentence as was a family member of Nang Nang Tai. Family sources told Myanmar Now that the journalists were initially accused of working for an unlicensed publication but when it was revealed that Kanbawza Tai was not among the publications that had their licenses revoked after the February 1 military coup, the reason given for their arrest was changed to spreading false news.

Yin Yin Thein, a freelance journalist, was beaten and arrested on November 18, 2021, after military and police forces conducted a violent raid at her home in Indaw Township of Sagaing Division. The authorities reportedly seized her laptop, phone and camera equipment and beat up members of her family. The journalist is a member of the Myanmar Journalists Association and was a regular contributor to the Monitor News Journal and Lightning Journal. Her current whereabouts and legal status remain unclear.

Ma Hmu Yadanar Khet Moh Moh Tun, a video journalist with the Myanmar Pressphoto Agency, and her colleague, photographer Kaung Sett Lin, were critically injured and subsequently arrested by the military forces while covering a peaceful anti-regime protest in Yangon on December 4, 2021. Both the journalists were injured when a military vehicle drove through the crowd of protestors and onlookers.

Turkey

Hatice Duman was arrested in July 2003. She was sentenced to life imprisonment on charges of managing a terrorist organization. She appealed her case before the Court of Cassation in 2012, but her appeal was rejected.

Ayşenur Parıldak was sent to prison in August 2016. She was arrested on charges of being a member of a terrorist organization, and sentenced to seven and a half years in prison.

Tülay Canbolat, correspondent for Sabah Ankara, was arrested in the scope of the Bylock investigation. She has remained behind bars since January 2020.

Egypt

Doaa Khalifa was put in Al-Qantar prison in 2020 by Egyptian authorities without interrogation. Her arbitrary detention was renewed without being questioned or moved to court. She still remains behind bars.

Vietnam

Tran Thi Nga (C) stands during her appeal at a local people’s court in the northern province of Ha Nam on Dec. 22, 2017.

Photo Credit: Vietnam News Agency/AFP/Getty Images

Huynh Thuc Vy was sentenced in November 2018 to two years and nine months in prison on charges of defacing the country’s national flag. The court ruled she would remain under house arrest until her young children reached three years of age, after which she would be required to serve her full term in prison.

Pham Doan Trang, RSF’s 2019 Press Freedom Prize recipient, was arrested on October 7, 2020, during a raid on a room that she was renting. Pham was forced to rent due to constantly being chased out by police, depriving the journalist of her right to a permanent residence. In December 2021 she was sentenced to nine years in prison on charges of “anti-state propaganda”.

Tran Thi Tuyet Dieu, independent journalist, was arrested in August 2020 on charges of “anti-state propaganda”. Her Facebook page, where she posted news and commentary, was reportedly taken down. On April 23, 2021, the court convicted the journalist under Article 117 of the Vietnamese penal code and sentenced her to eight years in prison for “creating, storing and disseminating information and materials against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam”. In September, a court of appeals rejected her plea and upheld the sentence.

Ethiopia

Photo Credit: Getty Images

Luwam Atikilti

Luwam Atikilti, a reporter for Ahadu Radio & TV, was arrested at her workplace on October 22, 2021. The arrests came after the channel aired an interview of an official, who spoke about the takeover of Hayk town in Amhara by the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), a rebel group that's been long engaged in a war with the federal government.

Meaza Mohammed, Roha TV founder and reporter, was arrested by security personnel on December 11, 2021. She was reportedly the third journalist to be arrested that week as the police ramped up arrests under the country’s state of emergency law. After security personnel in plain clothes arrested Meaza from her parents’ home in Addis Ababa they took her to her home and office and searched both premises. The journalist’s computer equipment was seized, according to her family. Reportedly, the police initially refused to offer any explanation for the arrest but then claimed they were holding Meaza at Sostenga for being unauthorized by the Ethiopia Media Authority. Dozens of journalists have been arrested since November 2, 2021, when the government authorities declared a state of emergency in response to the ongoing civil war against rebel forces allied with the Tigray Peoples’ Liberation Front.

Cambodia

Photo Credit: Omar Havana/Getty Images

Long Kunthea and Phuon Keoreaksmey, who worked for the environmental website Mother Nature Cambodia, were arrested on September 3, 2020. They face charges of incitement to commit a felony or cause social unrest. Their crime was investigating the decision to fill in part of Lake Boeung Tamok.

Burundi

Agnès Ndirubusa has been behind bars since December 2019. She was sentenced to two and a half years in prison and a fine of one million Burundian francs was imposed on her on charges of trying to undermine state security.

Laos

Photo Credit: Fojo Media Institute

Houayheuang Xayabouly was arrested in September 2019. She posted a video on Facebook that drew attention to the government’s negligence towards devastating floods in Champasak and Salavan. Houayheuang was jailed on charges of spreading propaganda against the Laos People's Democratic Republic, and trying to overthrow the party, state and government. She was sentenced to five years of imprisonment and a fine of 20 million kips was imposed on her.

Philippines

Photo Credit: AlterMidya

Frenchimae Cumpio was arrested, along with four human rights activists, on February 6, 2020. She was taken into custody during simultaneous raids across Tacloban city that targeted journalists and human rights activists. She was arrested after the military and police raided two offices of groups known for their leftist positions. The arrested individuals have been accused of illegal possession of firearms. She is still in pretrial detention.

Russia

Novaya Gazeta. Photo Credit:Georgy Shpikalov/TASS

Malika Dzhikayeva was arrested on March 9, 2020, on drug possession charges. She has since spent more than a year in state custody in a pre-trial detention center. Malika was sentenced by the Factory Court in Grozny on December 11, 2020 to three years in a general regime colony. The latest decision by the Supreme Court ruled that she will be transferred to a regime colony to fulfill the remaining time of her sentence.

Saudi Arabia

Photo Credit: REUTERS/Jacquelyn Martin

Maha Al-Rafidi was arrested during a crackdown on activists, journalists and writers across the kingdom on September 28, 2019. She has been kept behind bars since.

Syria

Tal al-Mallouhi has been in prison since December 2009. On February 14, 2011, the State Security Court in Damascus convicted Al-Mallouhi of divulging information to a foreign state.

Hong Kong

Apple Daily deputy chief editor Chan Pui-man leaves after the court appearance of chief executive Cheung Kim-hung and Apple Daily editor-in-chief Ryan Law at the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts on June 19. PHOTO BY ANTHONY KWAN/GETTY IMAGES

Chan Pui-man, an associate publisher of Apple Daily, was arrested several times in 2021 and has been held in pretrial detention since July 21 on charges of conspiring to collude with foreign powers. The police have reportedly cited 30 pieces published in Apple Daily, primarily opinion pieces and commentary urging foreign sanctions, as criminal evidence against the journalist. Media reports stated that the newspaper’s headquarters and homes of its executives were also raided, and police seized computers and documents.

7. Regional Review

Reporting remains challenging for women journalists around the world, facing detention, online threats, sexual threats and other violations, even murder. Women journalists in the Middle East are still facing overwhelming state pressure and Turkey with 238 cases was the largest contributor of violations against women journalists in the region.

Meanwhile, women journalists in North America were most frequently subjected to police brutality, expulsion, and organized troll campaigns. In Europe, most of the cases reported had to do with detention, physical violence and legal harassment, among other violations.

In Asia, women journalists experienced more pressure from power centers and targeted hate campaigns from troll armies as well as state suppression. In Africa detention and state oppression stood out as the most common tactics for suppressing critical journalists. Moreover, the abduction of women journalists continued in 2021.

Middle East and North Africa

In 2021 the CFWIJ recorded a staggering 291 cases of violations against women journalists in the region. Turkey, with 238 cases, was the largest contributor. Other countries of concern included Palestine, where the Israel Defense Forces were responsible for extensive violence against journalists, as well as Iran where the state continues to incarcerate women journalists.

Photo Credit: TGS

In Turkey, the number of incidents in 2021 increased by a horrifying 256.47% compared to the numbers CFWIJ reported last year.

Photo Credit: Evrensel Daily

Since the dismissal of Mechichi’s government, news media companies have been blatantly targeted. One day after the suspension of the parliament, the police stormed the offices of Al-Jazeera Arabic in Tunis.

In Turkey, the state has routinely weaponized its institutions in attempts to intimidate and silence women journalists reporting on state violence and official overreach. The most common tactics employed to target women journalists in the country were legal harassment, police brutality in the field, and arbitrary detentions. According to CFWIJ’s data, at least 96 women journalists faced legal harassment prompted by their work, 81 journalists were attacked in the field (the number includes physical assaults as well as other miscellaneous attempts to restrict access in the field) and 22 journalists were detained in Turkey in 2021. The number of incidents in 2021 increased by a horrifying 249.99% compared to the numbers we reported the previous year. For this very reason, CFWIJ has remained on top of the events unfolding in the country and has reported extensively on each violation. Our multifaceted coverage of Turkey includes issue-based reports, timeline of events, in-depth cases of specific journalists as well as regular updates on the ongoing court cases of women journalists.

In Palestine, the frequency of the attacks against women journalists by Israeli forces flared up significantly during May and June 2021. In addition to arrests and detentions, there were several reports of physical assaults, attacks with rubber bullets as well as tear gas bombs. Media correspondents were repeatedly monitored and persecuted while on duty. Several of these women reporters faced detention and/or harassment of some form for revealing facts and information. At least 20 Palestinian women journalists suffered some form of violation ranging from murder to street harassment in 2021. Israel’s aggressive tactics to silence critical press in the region led to the killing of Palestinian journalist Reema Saad. Sources on the ground confirmed that she, along with her husband and two children, was killed in an Israeli airstrike in Gaza city. Reema was four months pregnant at the time.

In Iran, years of war, political revolutions, international intervention, and the rise of the religious right-wing has given way to a political landscape where women, especially women journalists, find themselves increasingly vulnerable at the hands of racism, international Islamophobia, patriarchy and theocratic elements within its governance system. This year, CFWIJ recorded eight significantly harrowing cases of persecution of Iranian women journalists. Perhaps the one case that highlights the extent of threat faced by women journalists in Iran is that of prominent Iranian human rights activist and journalist living in New York, Masih Alinejad. Masih was the target of an international kidnapping attempt this year. Four Iranian intelligence officials have been convicted by the Federal Court in Manhattan for orchestrating the plot.

The MENA region thus remains a hotspot on our radar. Countries in the region not only target their own journalists but regional politics also lead to flare-ups that result in cross-border violence, the brunt of which is borne by women journalists.

North America

Journalist Jen Osborne was one of the many journalists who revealed the repression of the free press at the Fairy Creek on May 17. Photo credit: Mike Graeme.

“I'm relieved that sense prevailed and I'm unburdened by those legal obligations. But this development does nothing to remedy the harm that was done to my ability to report or to prevent police from using the same exact tactic again. Canada speaks in high terms about a free press until journalism becomes inconvenient for corporations and governments - it's time we all demand better.”

-Amber Bracken, Photojournalist, Canada

“We were at the Hidalgo metro station, and heading off to cover the women's march in Mexico City. When we were leaving the subway, a group of police officers surrounded us and detained Leslie, grabbing her hair. (…) The police fired tear gas which hit Sashenka and Leslie. They were both beaten and arrested. “

-Gabriela Esquivel, Photojournalist, Mexico

The CFWIJ reported 145 cases from North America in 2021. This year saw a 26.08% increase in violations against women journalists in the region compared to 2020, when we documented 115 cases. There were at least 96 cases of violations documented in the United States, 38 in Canada, and 11 noticeable cases in Mexico in 2021.

At least two women journalists were killed, 11 were attacked in the field, 11 were sexually harassed, 11 were physically assaulted, 35 were expelled from their jobs, seven were detained, at least seven women journalists faced threats to their well being, 35 women journalists were subjected to organized troll campaigns, five faced racist attacks and six journalists were verbally harassed. Other violations include workplace harassment, legal harassment, deportation, online harassment and other miscellaneous forms of state oppression.

One of the most tragic cases the CFWIJ reported in 2021 in the US was the murder of Lynn Murray. The photojournalist was killed in a mass shooting incident at a superstore in Colorado in March. Lynn was killed along with 10 others in the horrific shooting. A month later, on April 23, young journalist Aviva Okeson-Haberman was found dead in her apartment in Kansas. Reportedly, the journalist was hit in the head by a stray bullet shot through her window. Aviva was working for Kansas City’s NPR station at the time. Throughout the year, the CFWIJ also continued to monitor Black Lives Matter-related, and other racially charged, violations against women journalists in the country.

Meanwhile, Canada saw a vicious organized harassment campaign, which entailed deeply gendered and racially charged threatening emails sent to scores of women journalists of color. The campaign, sparked by a provocative tweet by right-wing politician Maxime Bernier inciting his supporters to “play dirty”, targeted at least 20 women journalists. Although Bernier’s tweet was later deleted for violating Twitter’s community standards, the damage was done. Bernier had gone as far as to dox critical women journalists and shared their personal details online. Despite widespread condemnation, the Canadian authorities took negligible action against those responsible for the online hate, threats and harassment women journalists of color were subjected to. Racial inequalities in Canada were also reflected in the escalation of police transgressions against women journalists covering ongoing protests by Indigenous land defenders in different parts of the country and violations against them.

Mexico remains one of the most difficult places in the region for women journalists to exercise their duties, recording the highest number of cases for physical assaults in the region. In March 2021, four photojournalists were assaulted and detained by the police in Mexico City. Graciela López of Agencia Cuartoscuro, Sashenka Gutierrez of EFE News, Gabriela Esquivel from Daily 24 Hour, and Leslie Pérez from Heraldo de México were covering the demonstrations held to commemorate International Women's Day in Mexico City. The celebrations turned into violent protests as the police deployed tear-gassed and started arresting participants. While covering the chaos, the photojournalists were attacked and handcuffed by the police.

Gabriela Esquivel, photojournalist at Daily 24 Hour, spoke to CFWIJ saying “at this time we were at the Hidalgo metro station, and heading off to cover the women's march in Mexico City. When we were leaving the subway, a group of police officers surrounded us and detained Leslie, grabbing her hair. I immediately came back and tried to help her. In response, the police officers pulled my hair, kicked me, hit me, took off my mask and my glasses. Graciela saw that and attempted to speak with the officers, trying to explain the situation. She was then also attacked. They threw us on the ground. We managed to get up and wanted to leave. However, the police fired tear gas which hit Sashenka and Leslie. They were both beaten and arrested. One of them was handcuffed and some of our photographic equipment was seized. Luckily we were able to get it back later on“.

On April 9, 2021, correspondent for Multimedios Television, Vianca Maleny Trevino Nevejar, was assaulted by police and detained in the early morning. The journalist was on assignment covering an assault incident at a beverage store with her cameraman, Raul Zuniga when she was confronted by the police. When police saw Vianca reporting on the spot, they immediately cordoned off the area. Police officers accused Vianca of disrespecting the space, crossing the yellow tape, and taking pictures.

North America remains a region of immense concern for CFWIJ. Read on below to know more about the violations we documented in these countries.

Latin America

"If the Cuban regime does not reconsider, or the world forces, the blood will flow, because the Cuban people have shouted out loud that they lost their fear.”

- Camila Acosta, Journalist, Cuba

Nicaraguan police officers move journalists to stop their monitoring of a raid on the house of opposition leader Cristiana Chamorro in Managua, Nicaragua, June 2, 2021. (Reuters/Carlos Herrera)

CN Radio reporter Katy Sánchez (left) and intern Alexandra Molina (right) were recently attacked by riot police while covering a protest. (Photos by Sánchez and Molina)

President of the Senate Juan Diego Gómez filed a defamation lawsuit against Cuestión Pública’s founders Claudia Báez and Diana Salinas on November 15, 2021.

The Coalition For Women In Journalism documented 30 cases of violations against women journalists in Latin America. This shows an increase of 66.6% compared to previous year when CFWIJ found 27 cases where women journalists were vulnerable to different threats.

Colombia recorded eight cases, the highest in the region, followed by Peru six cases, Cuba five cases, Ecuador three cases, Argentina three cases, while El Salvador, Nicaragua, Panama, Brazil and Venezuela recorded one case each.

Three trends of violations in Latin America are physical assaults with nine cases recorded, legal harassment with eight cases and threats to personal well being with three cases recorded. Other violations were state oppression with two cases recorded, detention with two cases, sexual harassment with two cases. The journalists were also attacked/impeded in the field, organised troll campaign, workplace harassment, abduction, sexual harassment and online harassment.

In Columbia, police viciously attacked Katy Sánchez and Alexandra Molina, reporters of Colombian independent RCN Radio, while they were covering anti-government protests in the capital, Bogota. Security forces impeded journalists from filming the protests and beat them. The incident took place in June.

In July, 2021, CubaNet journalist Camila Acosta was arrested following the demonstrations she covered.

Camila was intercepted by agents of the political police shortly after leaving her home when she was preparing to carry out personal meetings. Hours before her arrest, Acosta was covering the protests that took place in the capital against the Miguel Díaz-Canel regime. The journalist’s access to the Internet and the WhatsApp messaging app was restricted on July 11.

"If the Cuban regime does not reconsider, or the world forces, the blood will flow, because the Cuban people have shouted out loud that they lost their fear," Camila wrote in her last tweet before being arrested. “It is time to pressure them to leave power. If we give in now, we will have many more years of dictatorship," added the journalist.

Women journalists in Colombia also faced legal harassment. One case was recorded in November when President of the Senate Juan Diego Gómez filed a defamation lawsuit against Cuestión Pública’s founders Claudia Báez and Diana Salinas. In an investigative report, the journalists had revealed his alleged corruption and links with drug traffickers

The most recent case in the region occurred in Cuba where two unidentified masked men physically assaulted journalist Mabel Páez at her home. The journalist was beaten by two men who entered her house around 8:30 a.m on December 7 according to theCuban Institute for Freedom of Expression and Press (ICLEP). "My 19-year-old son had just left and suddenly I saw that two men with black masks entered the front door and went upstairs and beat me up without saying a word," the journalist told ICLEP. The assailants physically attacked the reporter and left severe injuries including a swollen chin, bruises, and scratches on her left eyebrow, mouth, nose, arms, and torso. Two fingers on her right hand were injured during the assault as well.

Europe

“I want to call photo editors and art directors of newspapers and magazines to look around and notice how many amazing, brilliant photographs are authored by women. I also want to point out that gender bias in the photography market is still alive and kicking.”

- Agata Grzybowska, Polish Photojournalist

Patricia Devlin, Journalist

CFWIJ spoke to Patricia Devlin who was targeted with death threats in Northern Ireland.

“There has long been a history of impunity in investigations into crimes against journalists in Northern Ireland, including those who have been murdered. It is deeply disappointing that that impunity still exists.”

- Patricia Devlin, Journalist

When CFWIJ evaluated 2021, an increase of 18.1% was observed in threats, violence and rights violations against women journalists in Europe compared to the previous year.

Marianna Spring

The year 2021 also proved to be a challenging one for press freedom in Europe. The CFWIJ documented at least 196 cases of violations against women journalists. In several instances the perpetrators were linked to the state and/or benefitted from the culture of immunity that persists around crimes against journalists.

The year saw physical violence against at least 38 women journalists while 46 of them were detained, 20 faced threats to their well-being, and two were subjected to some form of state oppression. 36 women journalists faced legal harassment, five were attacked in the field, five were sexually harassed, and another five women journalists faced verbal harassment. Finally, 20 women journalists were dismissed from their workplace due to abrupt shutdowns of media houses.

Most of these attacks happened in the Eastern part of Europe. Red hot on our risk map for women journalists were Belarus, Russia, Ukraine, Georgia and the United Kingdom. Since 2021, Belarus has had the highest number of violations against women with at least 48 cases recorded. Russia followed Belarus with 35 cases, Ukraine with 17 cases and the United Kingdom with 12 cases of threats and attacks against female journalists. France had eight cases while Kosovo, Albania and Italy had five. Bulgaria and Poland have four cases each. Azerbaijan, Greece, Montenegro and Slovenia witnessed three violations while Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Serbia had two. Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Malta, North Macedonia, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland reported one case each against women journalists.

After the dubious presidential election in August 2020, Belarus faced a fresh wave of press repression. Under authoritarian ruler Alexander Lukashenko’s administration, only this year alone 25 women journalists were detained and 16 of them legally harassed by office raids, confiscated equipment and baseless accusations. Eight women journalists continue to be detained while several other journalists had to flee the country. The charges against most journalists who continue to face systemic violence through state institutions have not been made public.

Katsyaryna Andreyeva and Darya Chultsova were sentenced to two years imprisonment in a minimum-security penal colony after being arrested while covering a protest rally in 2020. Continuing crackdown against independent news outlets in Belarus sharply escalated in May when police raided the homes of at least 15 journalists, six of whom were women. The journalists’ laptops, phones and equipment were also confiscated.Another mass police operation happened in July 2021 when security forces raided the offices and homes of independent journalists, expanding a new wave of crackdowns on opponents of longtime President Alexander Lukashenko. The office of US broadcaster Radio Liberty in the capital of Minsk was searched and simultaneous searches were also conducted to the homes of a journalist from the Polish TV channel Belsat and several local reporters. On May 24, Belsat TV programme host Arina Malinovskaya, who left Belarus due to possible persecution, was threatened with her relatives. Arina was called and threatened by the Belarusian authorities to return to the country. She was told that until her return, her relatives would be kept in detention.

Russia followed Belarus with similar actions against women journalists, where 16 were detained due to their journalistic activities, and nine were legally persecuted. The year started with harsh police violence against women journalists when on January 23, Novaya Gazeta’ Elizaveta Kirpanova, Al Jazeera’s Aleksandra Godfroid and the Echo of Moscow’s Daria Belikova were brutally beaten following an uprising in Russia. Vera Ryabitskaya of The Insider, was detained and tortured during her arrest in St. Petersburg. Natalya Zubkova, editor in chief for The Novosti Kiselevsk network, faced horrific threats on February 25. She was attacked by a man who grabbed her from behind and pushed her into the snow. The assailant threatened her with further attacks if “she dares to open her mouth again.” She had to flee from the country because of the security concerns and revealed her situation on YouTube on February 27.

Later in the year, the president of Russia, Vladimir Putin, issued sexist remarks against CNBC journalist Hadley Gamble during an interview. Putin implied that Hadley was too “pretty” to understand policy changes regarding the recent gas shortage in Europe. Upon being pushed on the question, Putin displayed visible annoyance, adopting a pointedly rude demeanor. The sexist behavior at the meeting was further amplified the next day when a Russian newspaper published a picture of Hadley alongside Putin which clearly objectified her.

Ukraine was another country where women journalists faced significant challenges. Ukraine's largest independent English-language newspaper, Kyiv Post, abruptly suspended operations on November 8 after its owner Adnan Kivan dismissed all staffers in the newsroom. The sudden dismissal came amid an ongoing disagreement between its real-estate tycoon Kivan and the publication's editorial team. More than 50 journalists, including 29 women media workers, employed by the 26-year-old newspaper were fired without notice.

Physical assaults on women journalists in Georgia were a cause of concern in 2021. In June, Georgia’s TV Pirveli reporter Nini Elikashvili and cameraman Papuna Khachidze were verbally and physically assaulted. The TV crew was deliberately attacked at Tsalka Municipality in southern Georgia while covering local protests. One person was arrested in connection with the assault. In July the situation got worse in the country when 54 media workers were physically assaulted by a far-right anti-LGBTQ group in the capital Tbilisi on July 7. The news crews belonged to 16 different media companies and at least 14 women journalists were among those attacked.

In Northern Ireland, just like 2020, award-winner journalist Patricia Devlin faced death threats. The journalist continued her legal struggle to bring the perpetrators of these crimes to account. On May 10, 2021, she was threatened with sexual violence against her minor son. On April 21, she was targeted on social media after her coverage of the actions of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

In the United Kingdom, mostly journalists were deliberately targeted online and exposed to sexist attacks. An award-winning reporter Marianna Spring, covering disinformation and social media for BBC News, was subjected to incessant online trolling. In March, journalist Natalie Higgins also shared her experience of the vicious online trolling that she has endured since entering journalism. Sonja McLaughlan was the third journalist who was targeted with vile online attacks following her coverage of a rugby match.

While in Azerbaijan three women journalists Ulviyya Ali, Nargis Absalamova, and Elnare Gasimova were verbally abused and physically assaulted by the police despite identifying themselves as media members. The journalists were attacked while covering a protest against the murder of 24-year-old Sevinj Maharramova. Maharramova was allegedly murdered by her husband leading to protests regarding the persecution of women in the country.

When CFWIJ evaluated 2021, an increase of 18.1% was observed in threats, violence and rights violations against women journalists in Europe compared to the previous year. Such an increase in a continent considered the cornerstone of press freedom raises deep concerns.

Asia

“The Coalition For Women In Journalism has been documenting the harassment and intimidation of female journalists around the world which helps highlight the various challenges they face. Networks like CFWIJ, therefore, play an important role in pressuring the authorities to act and protect journalists.”

-Ailia Zehra, Pakistani journalist

Photo Credit: Dhaka Tribune

Pham Doan Trang. Photo Credit: Vietnam Voice

Frenchimae Cumpio. Photo Credi: Alter Midya

Apple Daily Newsroom. Photo Credit:The New York Times

CGTN newsroom. Photo Credit: Financial Times

Agnieszka Pikulicka

Sophia Huang Xueqin. Photo Credit: South China Morning Post

Gulmira Imin. Photo Credit: VOA Editorials

Zhang Zhan. Photo Credit: Amnesty International

The Coalition For Women In Journalism documented 129 violations against women journalists in Asia, including five murders in Afghanistan. Other violations include 27 organized troll campaigns, 26 legal harassments, 20 detentions, 18 women journalists threatened with violence or intimidation, six women journalists were attacked in the field, six experienced physical assaults, five verbal harassments, three of them experienced state oppression and others were arrested, expelled, deported, etc.

With five out of 12, Afghanistan is the country with the highest number of murdered women journalists during 2021. Mursal Wahidi, Sadia Sadat, and Shahnaz Roafi, who were employed by Enikass Radio and TV, a news and entertainment platform, became victims to targeted killings on March 2, 2021. Mina Khairi is the fourth woman journalist killed in Afghanistan. Khairi was murdered in Kabul alongside her mother in an IED blast.

With the fall of Kabul to the Taliban, women journalists’ lives have been in danger. Being prohibited from work and seeking survival, many have managed to flee but a very long list still plead for help while evading the Taliban’s watch. CFWIJ has evacuated 270 journalists, activists, women rights advocates, and others from Afghanistan. However, there are hundreds more urgent cases in grave danger.

The CFWIJ has reported extensively on the threats and violations against women journalists in recent months in Afghanistan.

Outside of Afghanistan, organized troll campaigns and legal harassments lead the type of violations list in Asia.

A threatening and hateful video was posted on a YouTube channel on February 11, asking for the hanging of some notable journalists in India. The video was viewed by almost half a million people before it was taken down for violating YouTube’s policy on hate speech. The video accused journalists critical of government policies of having vested interests and financial incentives. The claims in the video were unsubstantiated, yet it was endorsed by many right-wing politicians.

Prominent right-wing politicians shared and endorsed the claims of the video. They later questioned how YouTube could take down the video, ignoring the dangers associated with demanding the execution of five journalists.

From Pakistan, the CFWIJ has observed a spike in troll campaigns against women journalists who question the state's brutalities and challenge its oppressive narrative. From state-level persecution to organized harassment campaigns, women journalists in Pakistan suffered it all. Difficulties for Tanzila Mazhar didn't ease even in 2021. She continued to face legal harassment despite medical complications.

For Asma Shirazi, this year was not just about organized troll campaigns. In fact her struggle to continue journalism became more intense when she was nominated in a petition for treason charges. Asma reasserted her commitment to her work and shared that she has faced all kinds of threats and pressure numerous times. While speaking with CFWIJ she said, this is the worst era for journalists in the country.

Another accomplished journalist who suffered the harshest of organized targeted campaigns was Gharidah Farooqi, who faced vitriol by members of the sitting government and its supporters. In the same year, Gharidah faced a cyber attack as someone tried to hack into her Twitter account. One prominent figure who was commonly observed attacking women journalists in the country was Prime Minister Imran Khan's focal person, Dr Shahbaz Gill. Mr Gill has a pattern of routinely attacking journalists which is then followed by troll campaigns.

Maria Ressa- the first Filipino Nobel Prize laureate faced constant legal harassment by the state. On December 9, 2021, Maria arrived in Oslo, Norway to collect the prestigious prize bestowed upon her and Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov “for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.”

Maria, who has faced persistent state-backed legal harassment for her fierce reportage, managed to attend the Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony despite the government’s attempt to prevent her from traveling abroad. She was permitted to travel to Oslo for five days after the courts thwarted the Duterte administration's block her travel and overruled the solicitor general’s contentions that the journalist was a flight risk.

Ahead of her arrival in Oslo, however, a senior member of the Philippine cabinet filed a new libel against Rappler, a digital media company for investigative journalism, which Maria co-founded in 2012 and still heads.

This lawsuit makes the eighth active legal case against Maria brought by the state. Find our detailed timeline of the attacks on Maria and Rappler here.

In Bangladesh, the CFWIJ extensively documented the harrowing experience of journalist, Rozina Islam. Rozina was wrongfully arrested on May 17, 2021, when she was at the ministry of health office, covering an investigative work assignment. She was accused of stealing confidential documents and was arrested later under the Office Secret Act of 1923, a notorious colonial-era law that prohibits access to sensitive information. Rozina was released after an international outcry but she's been facing legal persecution since then. Her passport and mobile phone remain with the state authorities. Her work accreditation has also been revoked. The CFWIJ launched a joint statement together with 23 international press freedom organizations to push Rozina's case and bring justice to her.

In Myanmar, the police and military officers arrested freelance journalist Shwe Yee Win in Pathein. Three days later on February 14, 74 Media broadcaster editor-in-chief Htoi Awng and camera operator Naw Seng, Mizzima News news website reporter Sai Latt Aung, and Eternity Peace News Network reporters Ko Wai Yan and Ko Yan Kaung were also arrested for covering a rally protesting the military coup in northern Kachin State. It has come to light that the five journalists were released after signing documents promising that they would not violate the curfew timings and the emergency laws prohibiting congregations of more than five people.

CFWIJ’s fellow member and freelance journalist Agnieszka Pikulicka faced various forms of violence by state officials including sexual harassment, threats of violence or intimidation, revoked accreditation, deportation and physical assault.

In November, Agnieszka Pikulicka was stranded for days after being denied entry into Uzbekistan by officials at the Zhibek Zholy-Gisht Kuprik border. Agnieszka was unreachable for more than 24 hours after being exposed to extreme cold without food and shelter for more than 48 hours.

Two women journalists were detained by the police on separate occasions during their coverage of the national elections in Kyrgyzstan.

Aliyma Alymova, a journalist for the independent news website Kloop, was attacked and detained in the city of Osh, alongside her colleague Bekmyrza Isakov. They were released without charge after three hours.

In Bishkek, another correspondent for Kloop, Aijan Avazbekova, was also detained while filming at a polling booth. The journalist remained in custody for two hours, after which she recorded a statement and was released. In both cases, Ayarbek and Aijan, the police claimed that the reporters did not have permission to film at the voting site. However, Kyrgyz laws on elections and referendums allow members of the media to film within polling stations.

Journalists Saniya Toiken of Radio Free Europe’s Radio Azattyk in Kazakhstan faced interference by the police while covering the parliamentary elections on January 10, 2021. She was among those whose phones were confiscated by the police. A police officer took Saniya’s phone and deleted some of the videos that she had shot in Nursultan on Election Day.

In October, 2021 HOLA News editor-in-chief Zarina Akhmatova and founders Alisher Kaidarov and Adilet Tursynbek were forced to resign after the website of the independent news network was made widely inaccessible for users. HOLA News was forced to remove its report on the Pandora Papers, implicating former president Nursultan Nazarbayev’s believed extra-marital partner Assel Kurmanbayeva as a beneficiary of secretive offshore payments, before its website was restored after 10 days.

Africa

Bukola Adebayo, WanaData Nigeria

“I don’t recall any organization or non-profit that is solely focused on the risks and dangers that female journalists face doing their job before CFWIJ.”

-Bukola Adebayo, Nigerian journalist

Algeria arrest of Kenza Khato © Sami K

In Ghana, journalist Zoe Abu-Baidoo Addo was tricked into coming to the police station after her colleague Caleb Kudah, who was investigating potential graft in the government’s dealings at the time, was arrested and beaten in May.