Reporting in the Dark: The Struggle of Pakistani Journalists Against Mobile Network Shutdown During General Elections

“All the work that I would otherwise do easily became immensely stressful because of connectivity issues” - Geo News reporter Kiran Khan

The third time was not a charm for Kiran Khan, a senior correspondent at Geo News — one of Pakistan’s most-watched news channels, who was covering a general election for the third time in her career spanning over a decade. The journalist has covered three major general elections in the country but describes her latest experience as the most frustrating of all.

“I’ve never faced the kind of issues I’ve been confronted with this time,” Khan tells Women Press Freedom. The journalist has been working as the broadcaster’s long-time reporter in Karachi, one of Pakistan’s largest urban centers.

Pakistan witnessed its 12th general election since gaining independence from United India in 1947. Through the years since its inception, the country has weathered political, economic and social challenges credited immensely to its dwindling democratic system that remains beleaguered by frequent interventions by its military leadership over the course of its 75-year-long existence.

“I’ve never faced the kind of issues I’ve been confronted with this time”

To date, the country has not seen a single democratically-elected government complete its five-year tenure without any challenges or interferences, including those by its own army, which — political experts claim — continues to influence the country’s political decisions and remains at the helm of affairs meant to be dealt with by a civilian government.

Despite immense anticipation surrounding the general elections, they stood out as one of the most contentious in Pakistan's history. One political party, specifically, was cornered ahead of the electoral process, as their founder Imran Khan remained incarcerated.

Rumors and predictions about the likelihood of polls being delayed were rife just weeks preceding the D-Day. But the country’s caretaker government managed to ensure its conduct amid speculations of postponement, escalating terror attacks, and accusations of victimization by Khan’s popular party.

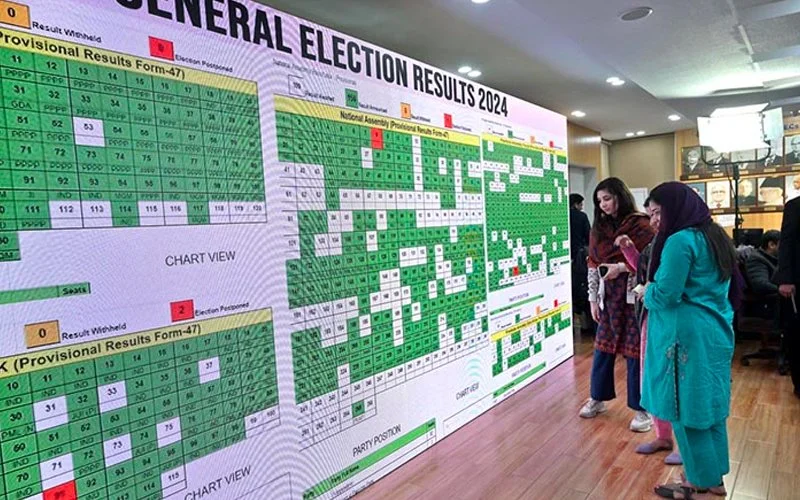

The elections were significantly marred by the caretaker administration's decision to shut down mobile networks nationwide on the day of voting, amplifying existing concerns regarding the transparency of the electoral process as well as violations of press freedom. These worries were validated when numerous journalists reported struggles in timely reporting on the proceedings of polls. The Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) issued accreditation cards to both local and international journalists to ensure ease of access to polling stations and offices of returning officers to observe vote count as well as collect results as they began arriving.

Before the elections, there were reports of journalists being attacked by hooligans in the poll campaign rallies of political parties. However, what happened on the day of voting, surpassed all press freedom violations, as a crucial means of communication was shut down on a countrywide basis, leaving a major chunk of the population deprived of receiving real-time and accurate reporting on a critical event.

To understand the gravity of ground realities, Women Press Freedom reached out to journalists in Pakistan who covered the February 8 general polls in the midst of political instability, fears of terrorism, and an overwhelmingly dominant caretaker setup.

‘No mobile signals’

Speaking with Women Press Freedom, Khan — who reported the general elections from two of Karachi’s constituencies — says there was a feeling that mobile networks would experience disruptions, but it wasn’t certain after all. The Geo News correspondent details how shortly after her 7 AM morning beeper duty with her channel, mobile signals vanished. The two constituencies that she was covering comprised over 600 polling stations.

"These were located far from where I could use the Wi-Fi. My house was in the middle of both constituencies, but the polling stations were far from my home,” she says, detailing how she faced trouble recording footage at the polling stations and rushed home to send them to the channel.

Khan adds that reporters are tasked with ensuring live coverage of the ground situation alongside a DSNG. However, she explains, that too became a tough nut to crack.

“I wasn’t able to coordinate and connect with them as there were no mobile signals. We only had an IFB earpiece with the DSNG through which we were coordinating with the channel but that too with a lot of difficulty since there were no mobile signals.”

“All the work that I would otherwise do easily became immensely stressful because of connectivity issues”

Another challenge Khan encountered was transferring all the footage made at the polling stations she was assigned to cover. To send this footage, she had to locate a place with Wi-Fi to file her story and tickers to the channel.

“In a way, all the work that I would otherwise do easily became immensely stressful because of connectivity issues,” she says.

The journalist’s apprehensions increased when the results of the polls began pouring in.

“It is impossible for us to be physically present at all locations, so we were supposed to be in contact with people who would provide us with the necessary documents and information regarding polling for us to assess the results. But we weren’t able to get them timely,” Khan says, adding that this, too, was a result of the lack of mobile networks.

“We weren’t able to strategize anything with the channel and take our own decision to send stories and footage timely. I did whatever I could within my capacity and domain,” the journalist explains.

‘Had trouble coordinating with boss’

Another Pakistani journalist, who wished to remain anonymous, was reporting from Islamabad for a foreign media agency. Narrating her ordeal in conversation with Women Press Freedom, she details how the lack of mobile signals made it difficult for her to coordinate with her boss.

“I got to the polling station before the polling began. When I was there, I had to get information about people, to report on it to my boss, but I couldn’t do that,” she says, adding that things worked out for her when she was able to get a call through her office’s landline.

The journalist was also unable to ensure the safety protocol of her news organization which included their on-ground correspondent to share their live location. This was how the journalist completed her preliminary story. But, she says, “it would have been much easier coordinating with everyone if there were mobile signals.”

‘Elections were chaotic, role of press irrelevant’

When specifying the issues he encountered on the poll day, Geo News Karachi reporter Waqas Alam Angaria termed the elections “chaotic,” particularly due to the blockade of mobile internet. He questioned how one can expect checks and balances and cover free and fair polls when a crucial service is shut down.

“There was no point in recording anything because you couldn’t send it as the mobile signals were shut down. The role of the press was irrelevant in this election,” he says, stating that everything people saw on television was produced with immense difficulty.

“The role of the press was irrelevant in this election”

The journalist explains that if he recorded “rigging” at any polling station, transferring it to the channel was challenging, as he had to commute for at least 20 kilometers to get Wi-Fi and then send all the materials to his team in the channel’s office.

He narrated that reporters saw rigging happening but couldn’t record anything without the technological services available.

“This was an entire violation of press freedom because the media solely relies on gadgets, and if you paralyze those gadgets, it is nothing. But despite these challenges, the press did its best job,” Angaria added.

“This was an entire violation of press freedom because the media solely relies on gadgets, and if you paralyze those gadgets, it is nothing”

The reporter tells Women Press Freedom that the police weren’t allowing him and his team inside multiple polling stations. “We had no way to get into it. How am I going to do anything when I don’t have internet? I can neither call the Senior Superintendent of Police nor my office.”

Angaria adds that the police kicked them out when the counting began. When he asked for relevant documents to check the results, their request was denied.

“The deputy commissioner’s office was cordoned off in multiple areas, especially in district central, and we were not allowed to go to the Keamari DC office. Also, candidates themselves violated a lot of [rules], as they came with their goons and started thrashing the ballot boxes,” he shares.

Angaria saw all the violations happening, but was unable to report it following the mobile network shutdown, detailing that covering the elections was a “horrible experience as a journalist.”

‘Nothing was transparent’

Maryam Nawaz Khan, Geo News Islamabad reporter, also narrated her troubles speaking with Women Press Freedom. Despite the issuance of accreditation cards by ECP, journalists were barred from entering polling stations and RO offices to collect final results. The reporter says she spent the whole day and the next morning trying to get the results from the constituencies she was assigned to cover by her bureau. And the mobile network shutdown worsened the situation for journalists, even in the country’s capital city.

“There was no internet. Therefore, the first issue was the hindrance we faced in reporting was due to that internet disruption,” says Khan.

The reporter specifies that with the possession of the accreditation cards, journalists were allowed to visit any polling station and offices dealing with electoral matters.

“We would have to sit at the RO’s office where they had placed three to four large LCDs and were supposed to air all the polling stations in real time on those screens. But they did not allow us entry into that office,” she says, despite following the electoral authority’s code of conduct.

Khan explains that at one point, she managed to enter a Ros office only after she did not identify herself as a journalist and walked in without showing her accreditation cards.

“It could have been a problem for me had someone found out who I was. But I went inside that office compromising on my security and made footage of the violations I faced… the security guards at the polling stations said journalists are not allowed inside, even though a journalist is permitted inside as per the law.”

“I went inside that office compromising on my security and made footage of the violations I faced… the security guards at the polling stations said journalists are not allowed inside, even though a journalist is permitted inside as per the law”

The journalist also reveals that she and many of her fellow reporters were denied the necessary documents to ascertain the results of the polls nor were the results being displayed in real time. Maryam says she and other reporters would have easily done their job if they hadn’t faced the hindrances.

“Even though they made claims of ensuring transparency, nothing they did was transparent,” she says.

“Even though they made claims of ensuring transparency, nothing they did was transparent”

The anecdotes shared by Pakistani journalists, particularly during the recent election, are a stark reminder of the hindrances they face while doing their jobs on an everyday basis alongside the alarming violations of press freedom in the country.

For any democratic nation to thrive, the role of the press and journalist community remains crucial, as their work not only involves reporting on unfolding events but also seeking answers to questions about the fair use of power and accountability for the public interest. Their contribution to unearthing the truth and presenting facts is significant, particularly in the midst of a disputed election where the chances of misinformation, disinformation, and mal-information are high.

It is important that the issues and fears raised by journalists in Pakistan in their conversations with Women Press Freedom are taken seriously with necessary measures to address the lack in the country’s press ecosystem.

While several political parties continue to raise concerns and challenge the results of the elections in the wake of “rigging” allegations, the points raised by journalists are alarming, particularly with regard to the disruption of mobile networks. These allegations by political parties as well as the issues pointed out by journalists, must be taken seriously and addressed by the incoming government, which will now take over the reins of the country.

Women Press Freedom is an initiative by The Coalition For Women In Journalism

The Coalition For Women In Journalism is a global organization of support for women journalists. The CFWIJ pioneered mentorship for mid-career women journalists across several countries around the world and is the first organization to focus on the status of free press for women journalists. We thoroughly document cases of any form of abuse against women in any part of the globe. Our system of individuals and organizations brings together the experience and mentorship necessary to help female career journalists navigate the industry. Our goal is to help develop a strong mechanism where women journalists can work safely and thrive.

If you have been harassed or abused in any way, and please report the incident by using the following form.